Use big data and predictive analytics to improve Health Outcomes

- Locations

- Middle East & Africa

- TB Preventive Treatment: the need of the hour for TB control in Africa

TB incidence and the End TB Strategy:

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major global health challenge, despite being preventable and largely curable. In 2022, TB caused approximately 1.3 million deaths worldwide, making it the second leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, after COVID-19. The World Health Organization's End TB Strategy aims to end TB by 2035, setting ambitious targets of a 90% reduction in TB incidence and zero deaths, disease, and suffering due to TB, compared to the baseline year of 2015.1 However, with an 8.7% reduction in TB incidence from 2015 to 20222, progress is significantly behind the targets set for 2035, including the intermediate milestone of a 50% reduction by 2025.

While newer drugs and treatment regimens have positively impacted the fight against TB, a strategy that can enable countries to achieve the End TB targets is TB prevention. This includes TB infection prevention and control (IPC), vaccination with Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine to prevent severe forms of TB in children, and TB Preventive Treatment or TPT. IPC and BCG vaccination have been used for decades and have played a significant role in TB prevention and control activities worldwide. Since1993, TPT in the form of Isoniazid Preventive Therapy (IPT) has been recommended for contacts of TB patients under six years of age and People Living with HIV (PLHIV). Despite this, the uptake of IPT globally has been sluggish.

The expansion of TPT to other population groups in the countries has emerged as a priority in the End TB strategy. Several modelling studies2,3,4 have shown the potential of TPT to significantly impact the trajectory toward ending TB. The need to adopt and expand TPT was further ratified at the United Nations High-Level Meetings (UNHLM) on TB held in September 2018 and then in September 2023. At the 2018 meeting, a target was set to provide TPT to twenty million individuals of all ages by 2022. By the end of that period, only 52% of the target was met, with 15.5 million people receiving TPT. Figure 1 gives a snapshot of the targets and achievements of TPT in different population groups for the period 2018-20222, and the targets set for TPT at the UNHLM 20235.

Figure 1: Targets and achievements (in millions) of TPT in different population groups

Source: WHO and Stop TB

It is estimated that approximately a quarter of the global population is infected with TB (latent TB infection or LTBI), with a 5-10% lifetime risk of developing active TB disease.6 This risk increases dramatically, to 50-70%, among PLHIV with LTBI. The use of isoniazid for the prevention of TB dates back to 1965, following recommendations by the American Thoracic Society for individuals with a positive Tuberculin Skin Test – a test used to detect the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes TB. Since then, advancements in clinical trials and research have led to the World Health Organization recommending various TPT regimens, including a 3-month regimen of weekly rifapentine plus isoniazid, a 3 month regimen of daily isoniazid plus rifampicin, a 1 month regimen of daily isoniazid and rifapentine, a 4 months regimen of daily rifampicin, or a 6 or 9 months regimen of daily isoniazid.2,9 A recent Rapid Communication from WHO in early 2024 announced forthcoming updates to the drugs and dosages used in TPT, reflecting ongoing efforts to optimize TB prevention.

TB incidence in Africa

The African region has made significant progress in combating TB, with most countries in the region showing an estimated reduction of more than 20% in the incidence rate as compared to 2015. Remarkably, South Africa stands out as the only high-burden TB country to have demonstrated a reduction in incidence by at least 50%. A quarter (23%) of the estimated 10.6 million people (95% UI: 9.9–11.4 million) who developed TB disease in 2022 were from the African continent. Of the eight (8) countries that accounted for about two thirds of the global TB cases in 2022, two are from Africa- Nigeria accounting for 4.5 % of the TB cases worldwide and the Democratic Republic of Congo, accounting for 3%. Around 6.3% of the incident TB cases in 2022 were PLHIV. The proportion of people with a new episode of TB who were living with HIV was highest in countries in the WHO African Region, exceeding 50% in parts of southern Africa.

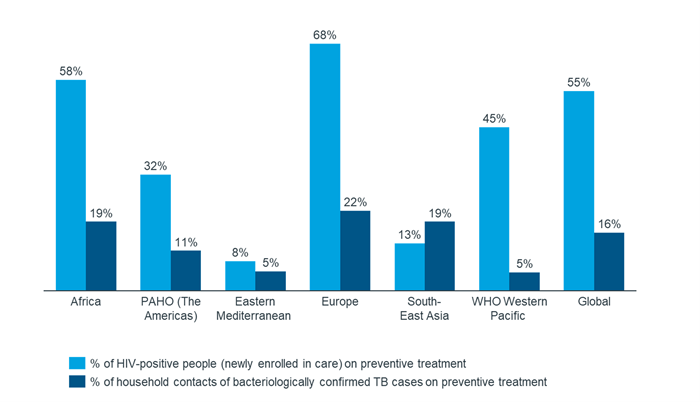

If we look at the various regions, with an incidence rate of 208 per 100,000 in 2022, the African region has shown the second highest incidence of TB after the South-east Asia region (TB incidence rate 234 per 100,000). Figure 2 shows the region-wise TB incidence rate and Figure 3 shows the global and region-wise TPT performance.

Figure 2: Region-wise TB incidence rates in 2022

Source: WHO

Figure 3: Region-wise TPT in 2022

Source: WHO

TPT in Africa

Majority of the countries in Africa have implemented TPT with most high burden countries having implemented TPT in PLHIV and household contacts of Drug Sensitive TB cases (DSTB) irrespective of age. Notably, South Africa is the only high burden TB country in the African region that has not yet implemented TPT for household contacts of DSTB patients, aged above 5 years.10

Despite great strides in the implementation of TPT for TB contacts, most countries are still performing sub-optimally and lagging in the achievement of UNHLM TPT targets. In many countries, ad hoc arrangement made for the procurement of 300 mg isoniazid tablets through the National TB Program have not been able to meet the need for drugs. Such logistical challenges ailing the supply chain in many African countries prevent the National TB Programs from tackling the increasing burden of TB infections requiring TPT.

Addressing the substantial burden of tuberculosis (TB) in heavily affected regions necessitates a multipronged approach. Effective management of TB involves not only the early detection and treatment of active TB cases but also robust measures to prevent new infections and halt the progression of latent TB infections to active disease. Implementing these preventive measures effectively will decrease the number of active TB cases in the community, thereby reducing the significant resources countries must allocate for the detection and treatment of new TB cases. TPT would, therefore, serve to “turn off the tap” by stopping new TB disease cases from entering the pool. Marking the World TB Day 2024 with a further stress upon the role of TPT in Ending TB, the World Health Organization (WHO) has released an investment case for the scale up of TB screening combined with TPT uptake. Dynamic transmission models were used to study the impact of these interventions on TB incidence, mortality and lives saved in four countries by 2050, including Kenya and South Africa, a snapshot of which is shown in Table 15.

Table 1: Impact of TB screening and TPT in African countries (2024-2050)

Way forward

Crucial steps need to be undertaken to sufficiently increase the uptake of TPT in the African continent if the region is to achieve its End TB goals. Figure 4 shows some key steps that can be taken up by countries for a successful roll-out / scale-up of TPT:

Figure 4: Steps to be undertaken for TPT roll-out

These steps have been described below.

Sustained political commitment and investments are critical for scaling up TPT. Each country can conduct impact estimations and transmission models to arrive at cost effective investment estimates that will help plan the finer details of the roll-out specific to each country, including the need for ‘test and treat’, target populations eligible for TPT etc.

Identifying target patients

- Enhanced contact tracing: Given the expanded scope of TPT in international and most national guidelines, increasing number of individuals will now be eligible for TPT including PLHIV, household contacts of DS/DR-TB of all age groups and other immunocompromised individuals such as those on dialysis, diabetics etc. Thorough contact tracing and screening will be needed to identify all close contacts of TB patients and initiating them on TPT after ruling out TB disease.

- Enhanced TB screening: Improved TB screening among people living with HIV as well as at the household level through robust active case finding, will not only serve to enhance TB detection and treatment but will also serve as a conduit to assess eligibility for TPT as per respective country guidelines.

Access to tests and treatment

- Testing for TB infection: Availability of diagnostic services such as TST, Interferon Gamma Release Array (IGRA) testing in countries adopting a ‘test and treat’ approach will be essential. Where needed, a robust sample collection and transportation system also needs to be established. Other tools such as Chest X-Rays should also be available to further help clinicians in ruling out active TB before the initiation of TPT.

- Unhindered access to TPT drugs: Additionally, increasing access to shorter TPT regimens will improve acceptability and uptake of TPT in the country. Resolving logistical challenges and ensuring an unhindered supply of drugs is critical to the success of TPT programs.

Programme management

- Adverse events management: Adverse events arising due to TPT should be detected and managed at the earliest. Individuals receiving TPT should be advised on the adverse effects to look out for and the steps that need to be taken if adverse effects are experienced. Care must be taken to rule out active TB disease before the commencement of TPT and a robust monitoring and reporting mechanism should be established in implementing countries to monitor adverse events or progress to active TB disease.

- TPT integration in country’s LMIS: Developing data collection modules to record TPT and integrating them in the country’s existing H/LMIS is imperative to provide the data needed to monitor regions, districts, and health facilities in a country. Integration of TPT in the country’s national monitoring and evaluation plan should also be prioritized, including the setting of national and sub-national targets. Cross linking registers for TPT and TB notification will further be beneficial by identifying TB patients who had previously been on TPT.

- Capacity building and Supportive supervision: of the healthcare workers to enable them to conduct screening drives and support and supervise the field/community level activities.

- Adherence management and counselling: Given that TPT recipients only have latent TB infection and not manifest TB disease, regular counselling should be provided and other methods to promote adherence such as mobile notifications and reminders from outreach workers can be adopted.

Demand creation and advocacy

- Advocacy: Strong advocacy campaigns, targeting both the healthcare workers as well as the general public are imperative for improving TPT uptake. Unlike TB disease which is symptomatic, ‘treatment’ of a latent infection will need clear messaging and community engagement. All advocacies should be contextual based on the population groups for which TPT is being implemented in the country, and the existing level of buy-in by program managers, healthcare workers, patient groups and even government ownership.

- Demand generation: Customized advocacy, communication and social mobilization strategies targeted to populations at-risk of acquiring TB infection and developing TB disease, such as household contacts of existing TB patients, PLHIV, other immunocompromised patients, healthcare workers in setting with high TB exposure, etc. should be rolled out. This will help in demand generation in each of the high-risk groups and will increase acceptability of the national program’s TPT activities.

Critical enablers

- Private sector engagement: As with TB diagnosis and treatment, efforts made to prevent TB disease through TPT are incomplete without reaching out to the patients seeking care for TB in the private sector. A thriving private sector in many African countries, including the high-TB burden Nigeria, indicate that a substantial proportion of TB patients also seek care in the private sector. Leveraging the available drugs sale data in these countries to prepare a private sector engagement plan will not only notify all TB patients seeking care in the private sector, but also help the National TB Programs to extend public health services such as TPT to the contacts of these TB patients, thereby, further tightening the control of TB disease.

- Data analytics and newer technologies: In addition to TPT modules integrated with existing LMICs, tools to collect, collate and analyze data at each step of the intervention will help the various systems, agencies and stakeholders involved through real-time analytics which can inform planning activities around screening campaigns, procurement of drugs and test kits, and even advocacy for high-risk populations. Newer technologies such as digital and AI guided Chest X Rays can further simplify the process of ruling out TB – an important step ahead of initiating individuals on TPT. Likewise, technologies such as Medication Event Reminder Monitor (MERM) Boxes can be used to support adherence in key populations at high-risk of developing TB disease.

Strong leadership and effective management will ensure successful TPT implementation which will positively impact TB control efforts by reduction of the TB pool in Africa. Gearing up to scale-up TPT, it is time the African continent joins the world to say ‘Yes! We can end TB!’

Dr. Almas currently works as Sr. Consultant, Public Health in IQVIA Middle East and Africa. In her current role, she has worked across multiple projects in Africa related to supply chain, health systems and immunization. She has previously worked at the Immunization Technical Support Unit (ITSU), Central TB Division of MoHFW India, and MSF.

1 End TB Strategy. World Health Organization. 2015

2 The End TB Strategy. WHO.

3 Wen, Z., Li, T., Zhu, W. et al. Effect of different interventions for latent tuberculosis infections in China: a model-based study. BMC Infect Dis 22, 488 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07465-5

4 Funding a tuberculosis-free future: an investment case for screening and preventive treatment. WHO. 2024

5 UNHLM 2023 Country Targets. Stop TB Partnership. 2023.

6 Comstock GW et al. The prognosis of a positive tuberculin reaction in childhood and adolescence. Am J Epidemiol. 1974 Feb;99(2):131–8.

7 World Health Organisation TB/HIV: a clinical manual for Southeast Asia. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1997. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63310

8 Runyon EH. Preventive treatment in tuberculosis: a statement by the Committee on Therapy, American Thoracic Society. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1965; 91:297–298.

9 WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis. Module 1: Prevention. Tuberculosis Preventive Treatment. 2020

10 Step Up for TB Report 2023. Stop TB Partnership.