The world’s fastest growing drugs are already facing Loss of Exclusivity in 2026

Semaglutide is the active ingredient in both Ozempic, an injectable agent for diabetes, as well as Wegovy, an injectable for obesity treatment. It is the world’s second-best selling prescription medicine, with combined sales of $26bn in 2024 and growing annually at a staggering 40%.

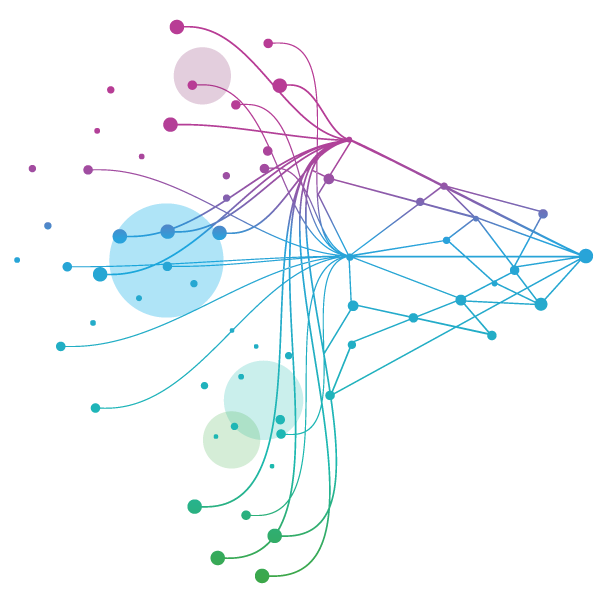

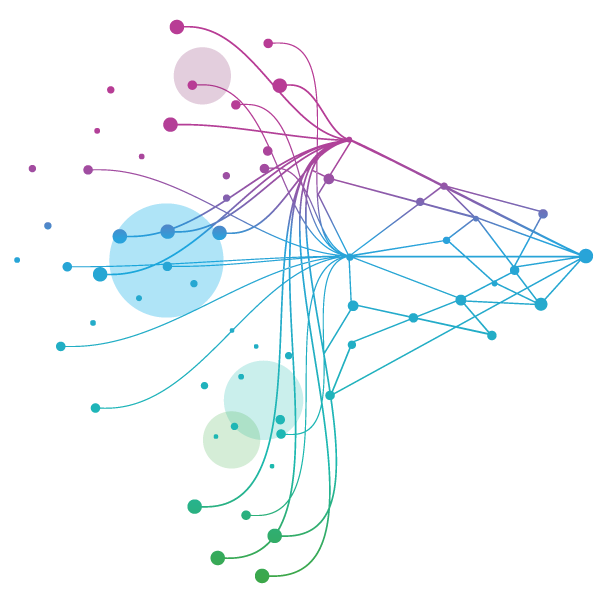

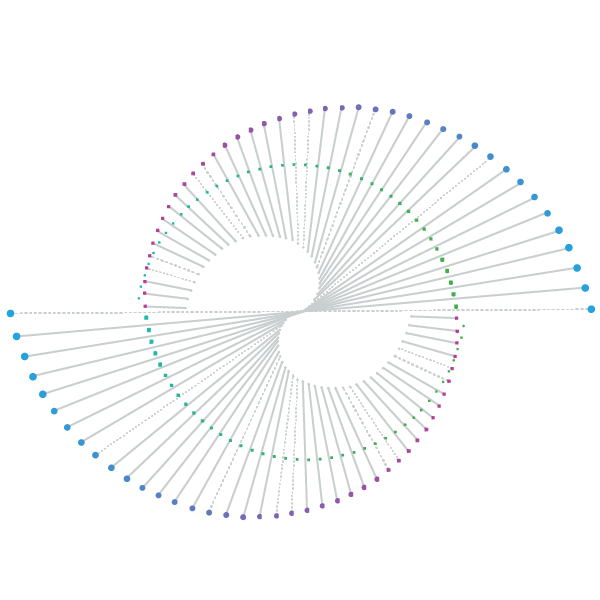

Semaglutide will be under patent in many countries until the early 2030s. However, its patent will expire in several countries starting in 2026. This includes large countries such as India, Canada, China, Brazil and Turkey which make up 40% of the world’s population and an estimated 33% of the world’s population of adults living with obesityi (see Figure 1). Interesting dynamics will be observed in each country, such as in India, where off-patent semaglutide will enter the market within a year of the launches of both Lilly’s Mounjaro (launched March 2025) and Novo’s Wegovy (launched June 2025), marking a short timeframe in which these originators can gain patient share before increased competition.

Given India's significant role in the generic pharmaceutical market, this development is expected to be positively received by manufacturers, healthcare providers, and patients. The Indian government's Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, which incentivises domestic manufacturing, has spurred significant interest from leading domestic pharmaceutical companies in developing their own version.

Over 10 companies have filed Subject Expert Committee (SEC) submissions in India to conduct Phase III studies for semaglutide, with 7 of them focusing on oral semaglutide, seemingly looking to differentiate away from the most common presentation. In addition, Indian companies have begun laying the groundwork for international expansion with Biocon partnering with Biomm who will file and commercialise their off-patent candidate in Brazil.ii

China is an equally formidable manufacturing powerhouse and there 17 candidates have progressed to PIII clinical trials or are in the pre-market application stage, with 9 of them specifically running trials in obesity. Amongst these manufacturers are competent players with prior experience in commercialising GLP-1s and so intense competition is anticipated in the coming years.

Implications for Non-Obesity indications

In diabetes, GLP-1 uptake in most countries is already well-established, with semaglutide enjoying reimbursement typically as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycaemic control. The anticipated arrival of off-patent semaglutide is unlikely to radically alter prescribing behaviour.

For example, in Canada, attention is already shifting towards newer entrants like tirzepatide (Mounjaro/Zepbound), which has demonstrated superior efficacy in weight loss in the head-to-head SURMOUNT-5 trialiii and is gaining momentum. On a broader scale, Canada seems to typically prefer switches to next-generation innovative biologics over a biosimilar/generic of an older agent.

Semaglutide’s off-patent entry could also reshape treatment landscapes in adjacent cardio-metabolic areas like heart failure, stroke and kidney disease. Its utility as a “backbone” therapy, with a broad range of risk reduction and treatment benefits may erode the market potential of newer, indication-specific therapies, even in areas where semaglutide is not yet explicitly approved, but initial trial readouts show promising results, e.g. metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH).

The obesity segment, however, presents a unique situation, with far less public funding, and evolving treatment norms. Here, the loss of exclusivity for semaglutide may drive more fundamental change.

Market Scenarios for Obesity Treatment

Several plausible scenarios could unfold as off-patent semaglutide enters the market:

1. Expansion of the private market

In most countries, where weight-loss treatments are self-funded, a lower-cost off-patent semaglutide could dramatically increase patient access, for example India and China are price-sensitive and with a dozen manufacturers developing off-patent semaglutide, this could create a surge in demand and expand the private market. Currently in China no GLP-1 products are included in the national or local medical insurance reimbursement lists, spurring originator companies to implement patient assistance programme and commercial insurance models to reduce OOP costs.

In Turkey, the preliminary expectation is that off-patent versions will not apply for reimbursements, with initial prices in the private out-of-pocket market expected to be very similar to the original product until competition drives prices down. The market is fast-moving and any unexpected competition may radically alter dynamics in the private market.

If appropriately marketed, off-patent versions could open the door to millions of new patients who were previously priced out.

2. Entry point for public reimbursement

Using the reduced off-patent price as a strong argument for increased access, Canada could become the first market with wide-scale reimbursement of existing primary care medicines, including GLP-1s for diabetes, to designate off-patent semaglutide as the first-line anti-obesity medication (AOM). If classified as a generic (rather than a biosimilar – likely dependent on whether the drug is synthetic or recombinant), Canadian pricing regulations could require discounts of up to 75% relative to originator products, unlocking new potential for public and private payers to cover the drug at scale.

Patient advocacy groups (like Obesity Canada) will likely intensify efforts to push for broader public and private insurance coverage, pointing to greater long-term healthcare savings and patient quality of life. They may also provide independent educational resources for patients navigating the various options on offer to simplify the treatment landscape with many options to hand.

3. “Maintenance” therapy of choice

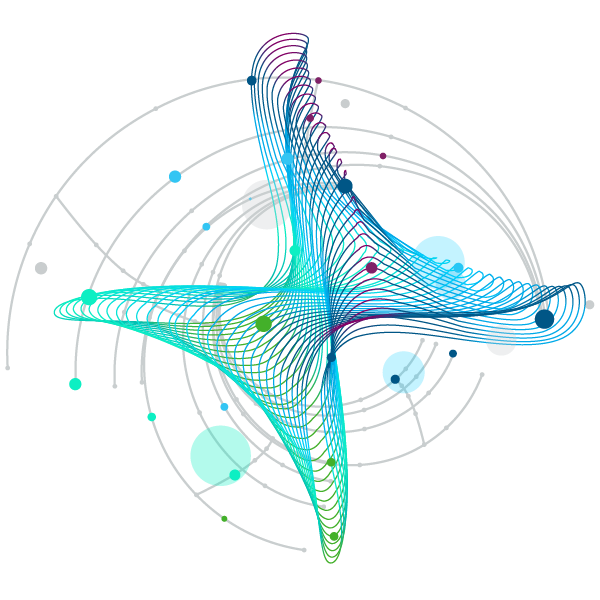

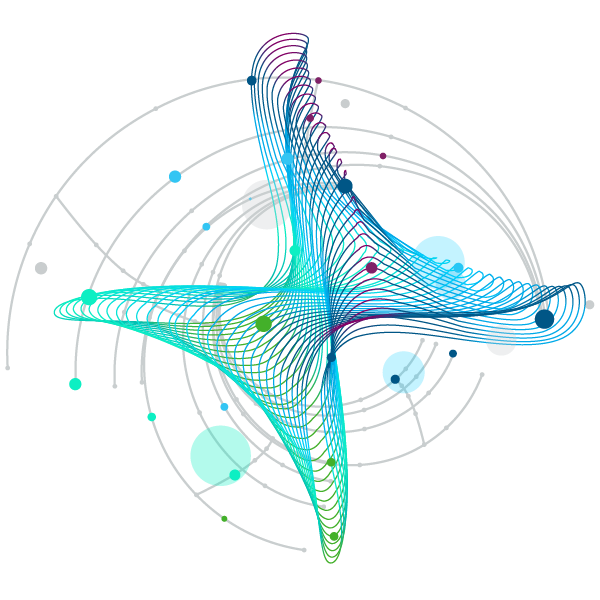

IQVIA’s recent study on 11,431 social media conversationsiv suggests that a third of all negative experiences with modern AOMs are due to cost concerns (see Figure 2). Lower priced off-patent semaglutide, with weekly dosing and adequate effectiveness, could serve this niche, leaving next-generation innovative products to focus on induction and early-phase weight loss.

This potential use would be informal initially, as there is very little or no formal clinical guidance on the use of pharmacotherapy to maintain weight loss, but as clinical trials have shown that people who discontinue AOMs typically regain weight, it is highly likely that real world use of these agents will include use to maintain weight loss and therefore that lower cost semaglutide may be preferred. Understanding of this use will come through real world data on AOM use.

4. "Starter" drug for new individuals

Some patients may experiment with low-cost semaglutide to “test the waters” before moving on to newer, more effective (in terms of initial weight loss) therapies such as tirzepatide or future orals like Lilly’s orforglipron. This could fragment patient journeys and intensify brand-switching behaviour.

5. High switching and price sensitivity

With affordability a primary barrier in the OOP market, patients may move fluidly between brands, generics, and suppliers in pursuit of the best value or simply availability. This dynamic will place a premium on patient retention and pharmacist relationships through branding and add-on services.

Strategies for Off-Patent Players

-

Pricing pressures

With multiple generic manufacturers expected to enter the market at launch, aggressive price competition is likely, particularly in countries where GLP-1 pricing remains high by international standards. Although the reimbursable market for liraglutide was short-lived in the UK as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agent, the experience with generic liraglutide saw rapid uptake by distributors with online pharmacy channels. Online pharmacies displayed various consumer-facing pricing strategies across their portfolio of weight-loss medications, with some large chains pricing the more efficacious Mounjaro below Wegovy in a bid to appear attractive to private patients.

In India, the competitive pricing from originals Wegovy and Mounjaro may not leave much headroom for discounting, but any lowering of price will be met favourably by price-sensitive patients. Hypera, a company looking to launch semaglutide into Brazil, commented that the price discount in South America’s largest market would be less than expected from generics due to high production costs and a low availability of injection pens.

Price competition in Turkey is expected to emerge with the second and third generics but is not projected to decrease more than 50% of the starting price. This competition is likely to take place in pharmacies through initiatives like free goods and discounts.

Although today’s semaglutide market is largely OOP, falling costs could tip the scales for wider public reimbursement where insurers may be more willing to cover AOMs, in addition to simplifying coverage by removing restrictions such as prior authorisation (see section above on public reimbursement).

-

Distribution channels and key stakeholders

Large wholesalers such as McKesson in Canada, serve closely aligned, and at times outright owned, retail pharmacy networks. They will play a decisive role in market access and will be a key negotiating interface between manufacturer and distributor.

Online pharmacies, where allowed, and digital health platforms could also become key players, as they facilitate a patient’s access to information and product in the private market. In China, medical aesthetics institutions and e-commerce platforms have emerged as strategic end points for manufacturers, and with consistent pricing and branding across channels, originators have been successful in forging partnerships with large, national players. A similar trend is observed in Turkey, where pharmacies play a key role in the competition for market share.

The emergent role of telemedicine and e-pharmacies as key stakeholders is exemplified in India, where platforms such as Tata 1mg are increasingly providing fulfilment services for rising consumer demand and concurrently facilitating the interactions between HCPs and patients.

Automatic pharmacy substitution rules will largely depend on semaglutide’s classification which depends on country by country. If treated as a generic, pharmacists will have more power to substitute prescriptions, accelerating uptake through price-based mechanisms, while if treated as a biosimilar, the decision on which brand is dispensed, under current common legislation, will typically lie with prescribers.

Despite the presence of off-patent alternatives, originator branding still matters in the private market. Consumers often search for trusted names like “Ozempic” and “Wegovy” and may default to known brands unless educated otherwise – a role that pharmacies and digital health platforms will need support with. Off-patent players may need to develop distinct, memorable branding strategies that support these activities.

-

Positioning and patient behaviour

People living with obesity increasingly self-direct their care given the long-term, chronic nature of their condition. Anecdotal evidence suggests this could express itself by stretching doses, delaying injections to manage OOP costs. However, with increased options of affordable semaglutide, higher-efficacy innovative originals and once-daily orals on the horizon, patients may be increasingly willing to mix therapies so tailor the benefit and side effect profile of their treatment. This would, of course, be a potential opening to risks of non-clinically endorsed treatment approaches, something which close monitoring of real-world data would be needed to understand. Multiple real-world studies are in the process of being commissioned to validate clinical promise in cardiovascular health and population-level economic benefits, but there is a gap where off-patent players can run their own studies to better understand choice, benefits and adherence across the many products to gain a deeper understanding across different presentations.

For off-patent semaglutide, competitive positioning will not hinge solely on price. A pivotal strategic decision for manufacturers will be the choice of presentation: whether to offer the product in prefilled pens, multidose vials, or oral formulations where feasible. The relative uptake of each form is likely to influence development investments, branding strategy and ultimately patient adherence.

With dynamic switches between molecules a real possibility, off-patent companies should aim to distinguish themselves by positioning their product specifically as a long-term maintenance agent, supported by wraparound weight management plans and digital adherence tools. In India, the price differential between the off-patent and original brands may be small, given existing aggressive pricing, and so robust RWE studies could give a differentiating edge, especially for companies developing oral semaglutide where the existing market is less established.

How might innovators respond?

Innovators are unlikely to sit idle. Novo Nordisk may attempt to mitigate the impact from off-patent competition by protecting their share of Wegovy by enhancing weight-management services, or migrating patients from semaglutide to newer, patent-protected AOMs, including offering an oral version of semaglutide, effectively offering therapies with greater patient benefits. Although Novo Nordisk will undoubtedly face price competition regardless as Lilly rolls out its orforglipron launch, the question is to what degree this will happen. They are unlikely to engage in public price cuts as this could affect other international markets, but they may offer confidential rebates or compete indirectly by launching authorised off-patent alternatives.

Lilly's actions could possibly focus on blunting the low-cost attractiveness of off-patent semaglutide with a competitively priced oral. Small molecule orforglipron could provide the lower COGS and financial headroom to do so and retain an acceptable margin. They could expand volume through the dual benefit of price elasticity of demand and the convenience of an oral therapy.

Other interested players may also benefit from the increased manufacturing supply by partnering with Indian manufacturers for co-marketing deals linked to expanding geographic reach in markets that are currently being underserved by existing players.

Conclusion: An inflection point in weight management

The loss of exclusivity for semaglutide in 2026 marks a strategic turning point in how players operate within the evolving AOM market. This shift has the potential to expand patient access, alter treatment pathways, and introduce new dynamics to how weight loss drugs are marketed. Importantly, it will provide a training arena, providing players with important data points on launching in and defending larger markets, as these inevitably lose semaglutide exclusivity in the early 2030s.

However, with a proliferation of manufacturers, the dangers of counterfeiting and substandard quality are likely to be multiplied. This presents a critical risk for patient safety that reputable manufacturers will need to address by working closely with regulators to ensure the security of the supply chain and robust quality control.

While the diabetes segment may see more muted changes due to existing reimbursement structures, obesity care is poised for transformation. The intersection of patient demand and new levels of affordability will reshape the competitive landscape and provide patients with greater access and healthcare systems improved delivery of care.

Assumptions

Given the uncertain nature of protection terms across different countries, the below points have been assumed to be true as a base to construct this article.

- Semaglutide will face loss of exclusivity in multiple countries in 2026, of which Canada, India and China are the biggest markets. Other prominent countries include South Africa and the UAE.

- Both Diabetes and Obesity indications will lose exclusivity, including oral versions

- At least 1 in 3 of people living with obesity in the world will live in a country with access to off patent semaglutide from 2026

- There is ambiguity around semaglutide’s classification as a generic or biosimilar, with many dependent factors such as the originator’s regulatory pathway and whether off-patent versions are synthesised or recombinant.

1 https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country

3 Tirzepatide as Compared with Semaglutide for the Treatment of Obesity Published May 11, 2025

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2416394

4 IQVIA social media listening study on AOMs between June 2024 and May 2025 where 11,431 conversations were sampled from the US and UK.