- Establish and continue relationships with the sites that will build trust

- Propose the right principal investigator and site grants

- Appreciate the cultural differences across regions

- Deliver key messages/philosophy for helping this patient population

- Maintain regular contact with the sites during the phase I study to keep screening patients during pauses

Despite having the most genetically diverse population and 25% of the world’s disease burden, Africa only hosted 4% of clinical trials globally in 2023, providing less than 2% of the data analyzed in genomics research. These trials were mainly focused on infectious diseases and restricted to phases III and IV, 1 limiting the coverage of noncommunicable conditions in which clinical innovation could significantly change population health outcomes on the continent. More clinical research in Africa can also improve access to lifesaving medicines and vaccines; strengthen the local healthcare ecosystem, infrastructure, and workforce capacity; make regulatory frameworks more robust; and open business prospects for private sector players. The key question is what factors could help lay the groundwork for a more inclusive clinical research landscape?

An inadequate healthcare setup and complex regulatory environment are often cited as the main reasons behind Africa’s underrepresentation in global trials, especially for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), rare diseases, and gene therapies, compared to global benchmarks. Insufficient national investment in other components of the healthcare value chain is also referenced as a major obstacle. However, trials addressing sickle cell disease (SCD) provide key evidence on how the capacity created through this research can be extended to other illnesses and therapeutic areas. Therefore, SCD is being viewed as a strategic entry point for strengthening Africa’s broader clinical research ecosystem. The relevance of SCD trials resides in their ability to mirror the complexity of many NCD studies, also requiring long-term follow-up, genetic and biomarker tracking, multidisciplinary care teams, and active community engagement.

Sickle cell disease trials as a driver of increased research capacity for other noncommunicable diseases

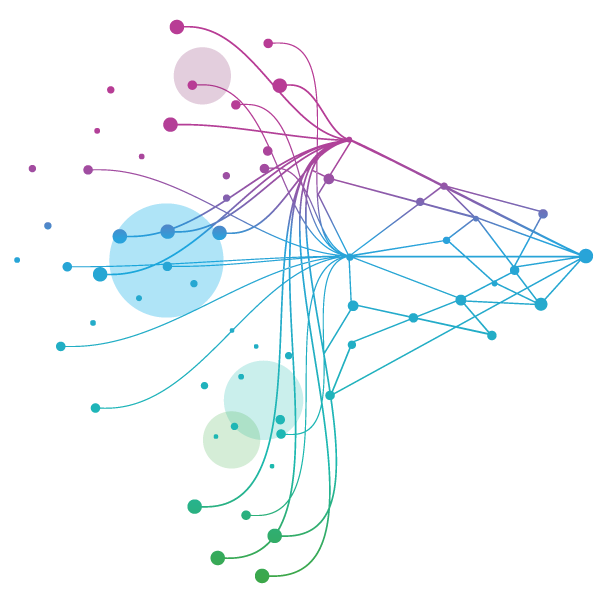

SCD, a hereditary red blood cell disorder notably prevalent in Africa and among populations of African descent, continues to be a pressing public health concern. Approximately 7.7 million people live with the disease globally, with over 300,000 babies born with the condition every year. While survival rates in the United States and Europe are higher due to improved specialized care and therapies,2 SCD still takes the lives of 376,000 people annually,3 particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). According to recent studies, cases have increased by 40% since 2000, and this trend could be exacerbated by current demographic trends in Africa, whose population could double up to 2.5 billion people by 2050.4 Beyond the clinical complications associated with this multifaceted and painful disease, including strokes, acute chest syndrome, organ damage, infections, priapism, and leg ulcers, people living with SCD are systematically stigmatized, adding psychological and social impact pressures to individuals and their families. Figure 1 summarizes epidemiological data about the disorder.

Figure 1. Overview of SCD epidemiology

Source: Thomson, A. et al. (2023). 5 Illustration produced by IQVIA EMEA Thought Leadership.

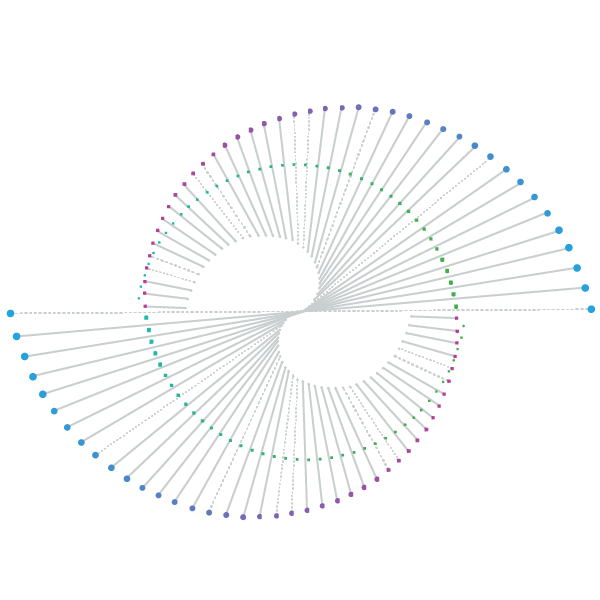

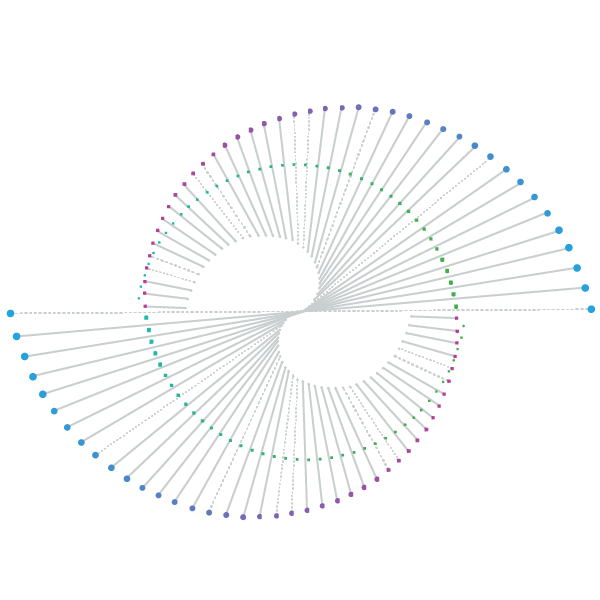

Responding to these and other epidemiological trends, the number of African research sites for the development of pharmaceutical innovations for SCD has been growing over the last few years. Research shows that between 1990 and 2024, the number of SCD enrolling centers across Africa increased from 0.5% to 13.5%, with a notable shift towards the early 2000s.6 In the last five years, IQVIA conducted 17 phase I through III global studies with 1,351 SCD patients in 26 countries, including Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda in Africa, as shown in figure 2. These studies have covered both adult and pediatric SCD patients and led to the accelerated U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory approval of two novel compounds in 2019. This pipeline evolution signals greater confidence in African research sites to support complex study design and meet global requirements.

Figure 2. IQVIA’s SCD clinical operations (phases I through III) between 2020 and 2025: 17 studies covering 1,351 SCD patients across 26 countries, including focus countries in sub-Saharan Africa based on disease prevalence

Source: IQVIA Research and Development Solutions and EMEA Thought Leadership

There are approximately 1,133 SCD studies registered in clinicaltrials.gov, 808 of which are interventional (in phases I, II, and III). 7 Clinical trials sites from Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda are well represented in these studies, with Senegal hosting four studies and Nigeria about 36. Since these studies are a key step in access to innovative medicines, experiences in these locations could influence how quickly treatments become available and contribute to enhanced efficacy and safety. This is particularly important as many key SCD therapies were not tested in the African population before their rollout, generating skepticism about their suitability. For example, hydroxyurea, the standard of care for SCD, first approved in 1998 by the U.S. FDA for both adults and children, required further evidence from the NOHARM 8 and REACH 9 local trials to demonstrate the drug’s value for African patients. In terms of upcoming solutions, it is expected that gene therapies, currently not available nor being investigated in Africa, can be further introduce through existing stem cell transplant centers in Nigeria and Tanzania.

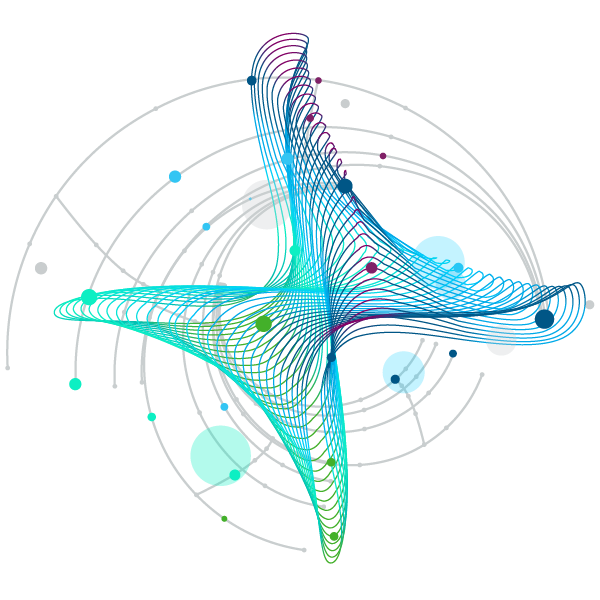

The progress made in SCD clinical research across Africa can open many doors for other NCD trials based on greater community participation and the local collaborations they harness. SCD trials are considering—and, in some cases, actively pursuing—a more prominent engagement of local researchers in clinical design, partnerships with central laboratories in the region to ensure the integrity of samples, faster recruitment of participants in high-prevalence areas, more training for healthcare workers, the strengthening of databases and registries, improved supply chains for investigational products and other supplies, and the establishment of adequate facilities. Figure 3 outlines the areas that IQVIA recommends keeping in mind in the design and implementation of SCD trials.

Recommendations for SCD trials

- Reduce patient burden using travel, meal and childcare reimbursement, and setting flexible visit schedules (weekends or after-hour clinics)

- Improve the patient-physician relationship to timely address concerns and aid compliance and develop communications tools to explain patients how to prepare for visits with detailed steps

- Provide appropriate payments for patients in the phase I study

- Study visit instructions for coordinators to ensure that assessments are properly sequenced

- Bring local teams experienced in working with fastest recruiting sites

- Set site visit triggers based on data as opposed to frequency (e.g., recruitment and protocol deviations)

- Plan for/perform soft-rolling locks to ensure data is cleaned on regular basis to allow for interim analysis and database locks

Figure 3. Recommendations for SCD trials

Source: IQVIA Research and Development Solutions and EMEA Thought Leadership

Furthermore, bringing the perspectives of people living with SCD into the picture enables the calibration of clinical research activities across the board by raising awareness of communities around the objectives and results of clinical trials (and even more so on what they entail), reducing dropouts, and listening more intently to their needs. During the Fifth Global Congress on Sickle Cell Disease in Abuja10 a representative from a patient advocate organization highlighted that trial participants are often faced with a lack of understanding about the research, lengthy trial periods, difficulties moving between rural areas and clinical sites due to costs and distance, interruption to work activities or school, and fear of side effects. Against this backdrop, community advocacy and support to participants are pivotal tasks and key success factors.

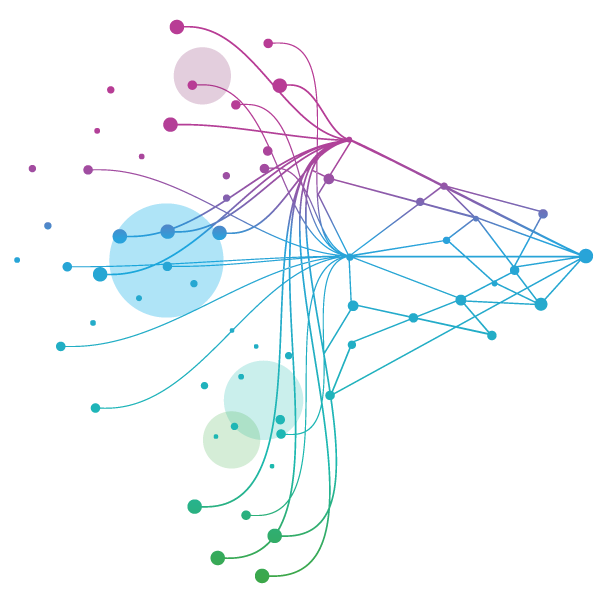

In summary, incorporating these considerations into the value chain of clinical trials with similar levels of complexity, focusing on those addressing cardiometabolic and oncological conditions, can attract new sponsors, expedite pharmaceutical discovery, facilitate access to vulnerable and underserved groups, and improve population health. In the case of NCDs, the sustained deployment of local innovation is extremely relevant and timely, considering that Africa is experiencing a considerable surge in the prevalence of—and mortality due to—these conditions. NCD-related deaths increased from 24.2% in 2000 to 37.1% in 2019, versus a decrease in those associated with communicable diseases.11 Figure 4 presents this trend and compares it with the current disease burden in Africa.

Figure 4. NCD-related mortality in the WHO Africa region (2000-2019), both sexes, and disease burden globally and in Africa in 2019

Source: WHO Global Health Observatory data12 processed by IQVIA EMEA Thought Leadership

Realizing a stronger clinical research ecosystem in Africa

The past five years have brought a quiet but meaningful change in how clinical research is regulated and executed in Africa. From harmonized regulatory frameworks to more collaborative ethics review processes, countries are steadily improving the predictability and efficiency of trial approval pathways. Organizations like the African Vaccine Regulatory Forum (AVAREF) and the African Medicines Agency (AMA) have accelerated cross-border regulatory alignment, offering a platform for joint reviews, reliance models, and faster timelines. For instance, Ghana’s FDA is implementing an accelerated review process for priority therapies, Rwanda has piloted adaptive oversight approaches, and Kenya is progressively adopting joint review mechanisms between its Pharmacy and Poisons Board and national ethics committees.

As of July 2025, Egypt, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe have achieved WHO Maturity Level 3 (ML3) status, indicating that their national regulatory authorities meet international benchmarks for quality, safety, and oversight of medical products.13 This level of maturity enables these agencies to lead and support multi-country trials that adhere to international standards. In tandem, many of these regulators are on a path to operationalizing reliance pathways, a mechanism that allows one authority to leverage the review work done by another trusted regulator to inform its own decisions. This approach, endorsed by WHO, will help accelerate clinical trial approvals while maintaining high regulatory standards in resource-constrained settings.14

Building on this momentum, the AMA is stepping into its role as a unifying continental force, with its first Director General appointed in June 2025. In May 2024, the AMA signed a memorandum of understanding with seven ML3-certified national regulatory authorities to strengthen collaboration on joint dossier reviews, shared inspections, and aligned reliance models.15 Egypt officially joined this alliance shortly thereafter. These efforts are reducing approval timelines, enhancing predictability and sponsor confidence in Africa’s ability to conduct high-quality, integrated clinical research at scale. Together, the convergence of regulatory maturity, regional reliance, and AMA’s leadership is transforming what was once a fragmented regulatory environment into one that is more aligned, efficient, and capable of catalyzing advanced clinical research activities.

These institutional and operational transformations are promising, but they are not applied consistently. Some countries still grapple with limited capacity, fragmented policies, or unreliable timelines. Yet, the appetite for reform is clear and supported by the evolving maturity of the clinical research infrastructure, reflected in the growing number of clinical sites and trials and the focus on novel therapies.

The importance of more clinical research in Africa: Investments as a win for all

Leveraging the capacity built through SCD trials, Africa’s vast experience in infectious diseases, and recent evolutions in the regulatory landscape can accelerate NCD-focused studies in disease areas like diabetes, breast cancer, obesity, stroke, and hypertension, all of which, as indicated earlier, are increasing in prevalence on the continent. Therefore, these trials are paving the way for a broader clinical research ecosystem and, as a result, facilitating the identification of much-needed answers for major public health threats.

This research landscape is also creating an optimal environment for home-grown solutions that are tailored to distinctive population needs and genomic specificities. More inclusive trials strengthen scientific validity, which is something that global researchers have acknowledged in recent years, especially in oncological care research, where African ancestry populations remain underrepresented. Access-wise, a stronger clinical research capacity enables patients in need to enjoy the benefits of new innovations faster. Studies have shown that the presence of clinical trials in African countries correlates with increased drug approvals.16

Community ownership does not only improve trust in these interventions but also serves as a conversation starter that raises awareness on specific diseases and exposes patients to positive health outcomes. For instance, IQVIA’s experience in investigating the use of paliperidone palmitate in Rwanda for schizophrenia reveals that placing communities at the center—that is, understanding the impact of a given condition through the voice of patients and making them part of the solution—can have positive effects on local buy-in, the retention of trial participants, and access to care.17 Similarly, the engagement of communities and patient organizations in SCD studies has contributed to the fine-tuning of clinical research operations in countries like Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya and Tanzania. Therefore, the perspectives of patients should remain pivotal as part of the advocacy efforts to bring more NCD trials to Africa.

Finally, investing in clinical trials goes beyond product pipelines and trial placement. Structured funding and capacity-building can deliver countless knowledge assets, empowered and more skilled investigators, and bolstered local ownership.18 In the case of neglected diseases alone, it is estimated that every dollar invested in clinical research has a return of US$405 in wider societal and economic gains. Taking a retrospective look, the same study indicates that product development in Africa between 2000 and 2022 has averted nearly 600 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a favorable outcome that could be expanded if the right conditions continue to be in place.19

Keeping this momentum requires scaling up investment in clinical research infrastructure and workforce capacity, maintaining the impetus behind regulatory progress, and driving stronger partnerships that support truly inclusive, diverse, and impactful trials. By moving farther in this direction, high-quality clinical research in Africa will drive more than just groundbreaking pharmaceutical discoveries: it will ultimately foster much healthier, economically vibrant, and resilient societies.

References

1 Tshilolo, L. et al. (2018). Hydroxyurea for children with sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa. The New England Journal of Medicine, 380(2), 121-131. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813598

2Aygun, B. et al. (2024). Hydroxyurea dose optimization for children with sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa (REACH): extended follow-up of a multicenter, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Hematology, 11(6), E425-E435. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanhae/article/PIIS2352-3026(24)00078-4/abstract

3 Thomson, A. et al. (2023). Global, regional, and national prevalence of mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000-2021: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease study 2021. The Lancet, 10(8), 585-599. DOI: 10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00118-7

4 International Monetary Fund (2023). A demographic transformation in Africa has the potential to alter the world order. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/09/PT-african-century#:~:text=The%20United%20Nations%20projects%20that,world's%20population%20will%20be%20African.

5 See reference 3.

6 Costa, E. et al. (2025). Globalization in clinical drug development for sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology, 100(1), 4-9. DOI: 10.1002/ajh.27525

7 ClinicalTrials.gov (n.d.). Search for sickle cell card results. Retrieved on July 7, 2025. Search for: sickle cell | Card Results | ClinicalTrials.gov.

8 Opoka, R. Et al. (2020). Hydroxyurea to lower transcranial Doppler velocities and prevent primary stroke: The Uganda NOHARM sickle cell anemia cohort. Haematologica, 105(6), 272-275. DOI: 10.3324/haematol.2019.231407

9 See reference 2.

10 Sickle Cell Support Society of Nigeria and Global Sickle Cell Disease Network (2025). Fifth Global Conference on Sickle Cell Disease. https://www.globalsicklecellcongress.com/

11Barry, A. (2025). Noncommunicable diseases in the WHO African region: Analysis of risk factors, mortality, and responses based on WHO data. Scientific Reports, 15. DOI: doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97180-3

12 World Health Organization (n.d.). The Global Health Observatory. Search for number of deaths caused by NCDs in the WHO Africa region. Retrieved on August 5, 2025. https://www.who.int/data/gho

13 World Health Organization (2025, August 7). Regulatory system strengthening: WHO-listed authorities. https://www.who.int/initiatives/who-listed-authority-reg-authorities

14 Valentin, M. (2020). Good reliance practices in regulatory decision-making: High-level principles and recommendations. WHO Drug Information, 34, 201.

15 See reference 11.

16 Strüver, V. et al. (2021). Patient benefit of clinical research in diversely advanced African developing countries. Current Therapeutic Research, 96, 100656. DOI: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2021.100656

17 Mora-Brito, D. (2024). IQVIA Africa Health Summit 2023. Executive summary. IQVIA. https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/mea/brochures/iqvia-africa-health-summit.pdf

18 Addo, J. et al. (2020). Supporting the next generation of noncommunicable disease research leaders in Africa. The experience of the GSK Africa NCD Open Lab. Journal of Global Health Reports, 4. DOI: 10.29392/001c.12274

19 Impact Global Health (n.d.). The impact global health R&D. Retrieved on August 5, 2025. https://impact.impactglobalhealth.org/research-investment