Discover new approaches to cardiovascular clinical trials to bring game-changing therapies to patients faster.

Introduction: Quality vs. quantity of weight loss

The treatment of obesity has been transformed by the advent of highly effective, incretin-based pharmacotherapies, which can deliver weight loss of 15-25% after one year.

Understandably, such impressive weight loss has dominated the headlines and captured people’s attention. However, it is equally important to consider the quality of weight loss to understand the effect these new anti-obesity medications (AOMs) have on patients’ overall health, for example, improvements in cardiometabolic risk factors such as lipids, blood pressure and glucose levels, or their impact on body composition.

Typically, reductions in weight lead to the loss of both fat and some lean mass, which comprises skeletal muscle mass. Given the unprecedented potency of the new AOMs, there is a particular concern about pharmacotherapy-induced weight loss resulting in potentially excessive loss of lean mass, including skeletal muscle, especially in vulnerable patient populations, e.g., those at risk of sarcopenia – the progressive loss of muscle mass, muscle quality and strength as a result of the human aging process.

Skeletal muscle plays an important functional and metabolic role. Not only is it essential for physical strength and mobility, skeletal muscle mass is directly linked to greater insulin sensitivity, a higher metabolic rate and an improved overall metabolic profile.

Absolute and relative loss of total lean body mass, assessed via DXA scan, is often used as surrogate endpoint for measuring the impact on muscle mass, despite its obvious limitations, e.g., including the weight of organs, bones, tissue and fluids in addition to muscle.

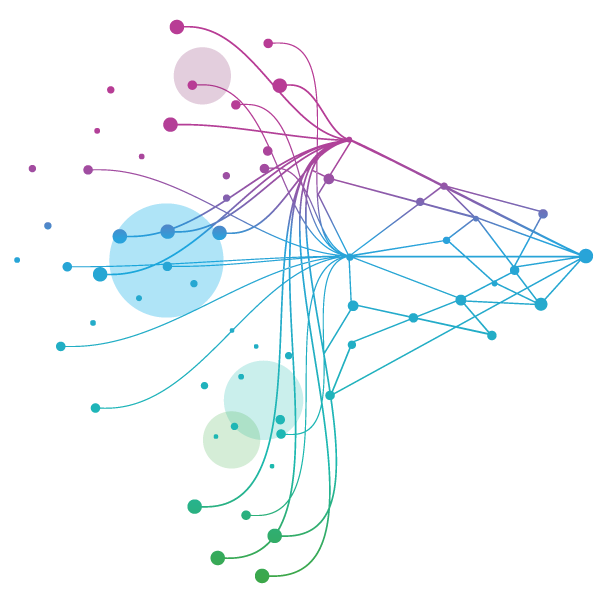

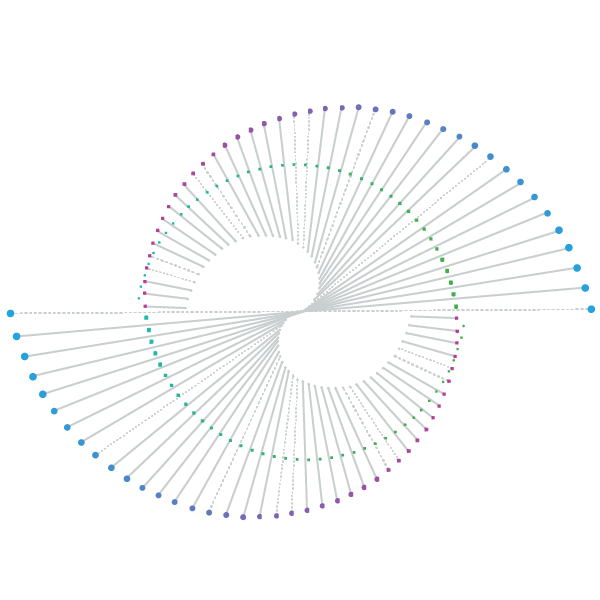

While most clinical trials of AOMs focus on measuring weight loss alone, the effect of AOMs on lean body mass was reported in a number of trials, which found that lean mass accounted for 15-45% of total weight loss (see Figure 1).

It is worth noting, however, that these clinical trials did not assess the impact of weight loss, including concomitant loss of lean body mass, on individuals’ physical function, the ultimate measure of patient-relevant outcomes.

The latest FDA draft guidance for developing drugs and biological products for weight reduction, published in January 2025, references the effect of AOMs on body composition and recommends measuring it, however, it does not consider the typical loss of lean mass harmful [1].

Specifically, the draft guidance stipulates that “In pharmacological trials, reduction of fat mass has typically accounted for 60% to 90% of weight reduction, and the accompanying reduction in lean mass has not been considered adverse. To ensure that […] weight reduction is caused primarily by a reduction in fat content, not lean body mass, a representative sample of trial subjects should have a baseline and follow-up measurement of body composition by DXA or a suitable alternative.”

When undue muscle loss becomes a problem

Sarcopenia, the progressive, aging-related loss of muscle, contributes to the development of physical frailty, including weakness, fatigue and balance problems which limit a person’s mobility and increase the risk of falls, fractures and other serious injuries.

Sarcopenia can occur alongside obesity and may be worsened by the accumulation of body fat. Termed sarcopenic obesity, it is characterised by the concurrent decline in muscle mass and function along with increased levels of adipose tissue and is associated with higher risk of disability, metabolic dysfunction, comorbidities, e.g., T2D, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality [2, 3].

The co-existence or these two independent disease states strongly increases with age, and also with body mass index (BMI) regardless of age, making sarcopenic obesity a fairly prevalent condition.

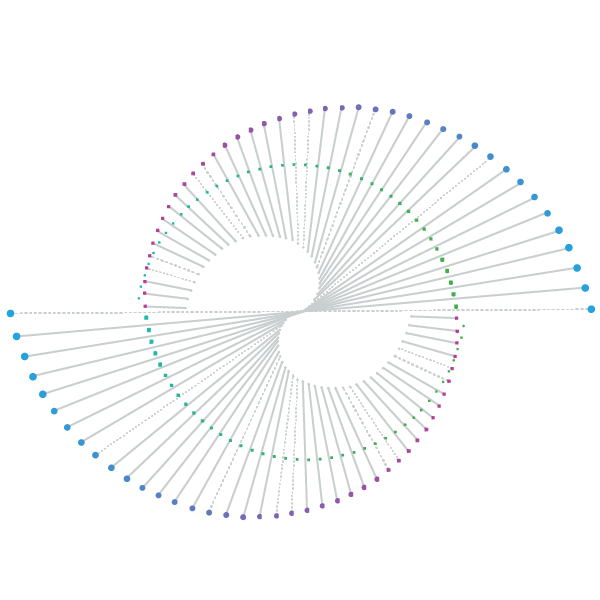

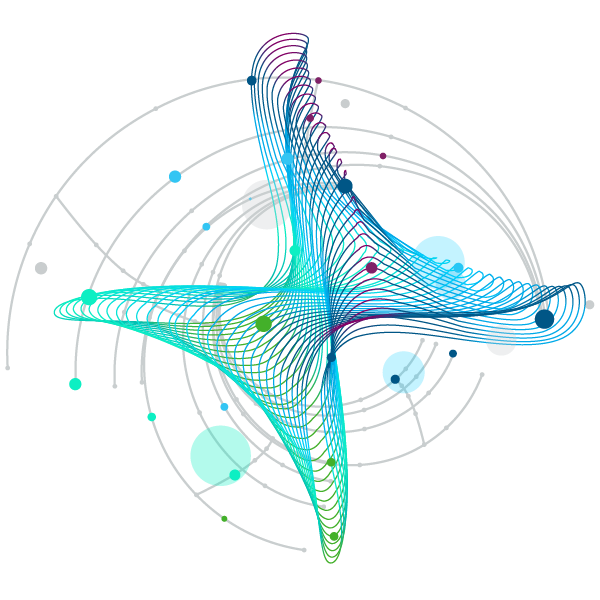

This trend was demonstrated, for example, in a cross-sectional study using data from the CDC’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) which analysed the prevalence of sarcopenic obesity in the U.S. population [4].

Note, in this study sarcopenic obesity was termed ‘obesity with low lean muscle mass’ (OLLMM), with obesity defined as BMI ≥27. Low lean mass associated with weakness was established by applying criteria from the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health to measurements of appendicular lean mass from DXA scans. Key findings from this study include (see Figure 2):

- Prevalence of OLLMM by age increases from 5.1% for age group 20-29, to 12.5% for age group 50-59, 20.2% for age group 60-69, 36.8% for age group 70-79, and 38.7% for age group ≥80.

- Prevalence of OLLMM by BMI increases from 9.2% for BMI from 27 to <30, to 21.2% for BMI from 30 to <35, 32.3% for BMI from 35 to <40, and 35% for BMI ≥40.

- Overall prevalence of OLLMM is estimated at 15.9% of the U.S. population.

When treating such high-risk populations with incretin-based pharmacotherapy for weight loss, preserving muscle mass is crucial for preventing frailty, obesity-related comorbidities, maintaining metabolic health and improving physical function.

To date, no formal guidelines exist for treating older, obese adults with the new AOMs, leaving HCPs to carefully consider, on a case by case basis, the benefits of AOM therapy vs. risks, including the consequences of further loss of lean mass, especially in frail, sarcopenic patients.

At the same time, options for minimising muscle loss are currently limited to non-pharmacotherapy interventions, e.g., increased protein intake and dietary supplements combined with endurance and resistance exercise during AOM-induced weight loss.

New approaches for addressing muscle loss

The emerging recognition of undesired muscle loss associated with incretin-based treatment of obesity as a potentially serious problem, especially in some populations, has spurred a growing interest in developing pharmacotherapies that can address this issue.

To this end, innovators are exploring two fundamental therapeutic approaches to preserve or improve muscle:

- Therapies directly acting on muscle growth to mitigate the effect of incretin-based AOMs; for example, by targeting the myostatin/activin signalling pathway, the dominant pathway regulating muscle homeostasis; or using selective androgen receptor modulators (SARM) to promote muscle growth, improve physical function and stimulate lipolysis to augment loss of body fat.

- Therapies facilitating more selective weight loss to minimise undesired muscle loss in the first place; for example, activating the leptin receptor to modulate energy homeostasis, e.g., reducing appetite while also blocking the response signal to reduce energy expenditure to enhance weight loss, utilise fat stores and thus preserve muscle; apelin agonism to increase energy expenditure, promote muscle metabolism and reduce fat accumulation; or mitochondrial uncoupling to accelerate metabolism and steer fuel preference towards fatty acids for selective weight loss which preserves muscle mass.

The current pipeline of investigational, muscle-preserving therapies comprises 32 assets, of which 47% are at preclinical stage, 22% in phase 1 and 31% in phase 2, as the most advanced candidates. To date, no muscle-preserving future therapies have reached phase 3 yet, however, several assets are poised to move into phase 3 in the near future, for example, Veru’s enobosarm, Rivus Pharmaceuticals’ HU6 or Lilly’s bimagrumab.

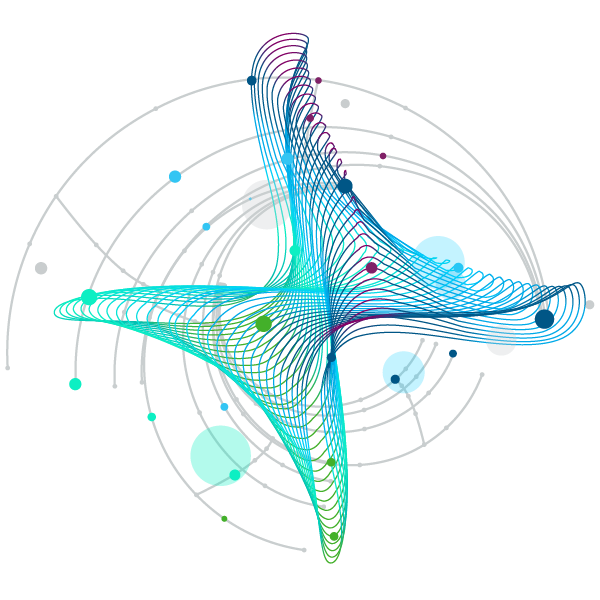

Unsurprisingly, the majority of innovators focus on the myostatin/activin signalling pathway given its pivotal role in controlling muscle growth, with assets targeting activin and myostatin accounting for 41% and 25% of the pipeline, respectively, or two-thirds collectively. Other noteworthy mechanisms of action among muscle-preserving assets include mitochondrial uncouplers (9%), apelin agonist (6%), selective androgen receptor modulator (3%) and leptin receptor agonist (3%) (see Figure 3).

Monoclonal antibodies lead the pipeline of muscle-preserving therapies with a share of 31%, followed by oral, small molecule therapies at 25%. Innovators are also exploring novel modalities to address muscle loss, including siRNA therapies and bispecifics, which represent 16% and 13% of the pipeline, respectively, with other biologics accounting for the remainder.

While some muscle-preserving assets have also delivered weight loss in their own right as mono-therapies, e.g., bimagrumab, their most promising application is nonetheless as adjunct therapies to incretin-based AOMs to synergistically improve body composition. This positioning is reflected in the fact that many innovators choose to investigate their muscle-preserving assets in combination with semaglutide or tirzepatide in clinical trials.

Highlights from mid-stage clinical trial readouts

Over the past nine months, several innovators have reported intriguing data from phase 2 clinical trials investigating their respective muscle-preserving assets. Noteworthy examples include:

Veru, phase 2b QUALITY trial: selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) enobosarm plus semaglutide [5]:

- Enobosarm in combination with semaglutide demonstrated statistically significant benefit in preserving total lean body mass at 16 weeks, with 71% relative reduction in lean mass loss vs. semaglutide plus placebo.

- Enobosarm plus semaglutide delivered similar mean weight loss vs. semaglutide plus placebo.

- Selective weight loss: 0.9% total body weight loss due to lean mass for enobosarm plus semaglutide vs. 32% for semaglutide plus placebo.

- Preserved physical function: 62.4% relative reduction in patients with ≥10% decline in stair climbing power for enobosarm plus semaglutide vs. semaglutide plus placebo.

Following its positive phase 2b readout, Veru plans to move enobosarm into phase 3. Veru has indicated a similar trial design to assess enobosarm in combination with a GLP-1-RA, with focus on functional endpoints and body composition, e.g.,

- Improvements in physical function measured by the Stair Climb Test at 24 weeks.

- Effect on total lean mass, total fat mass, insulin resistance, HbA1c at 24 weeks.

- Beyond the 24-week trial duration, continue monitoring endpoints to capture longer-term benefits of enobosarm.

Rivus Pharmaceuticals, phase 2a HuMAIN trial: controlled metabolic accelerator HU6, in patients with obesity-related HFpEF [6]:

- HU6 demonstrated significant weight loss from baseline (-6.8 pounds, p<0.0001); and significant weight loss vs. placebo (-6.3 pounds, p=0.003), at 19 weeks.

- Significant reduction in fat mass from baseline with HU6 (-7.4 pounds, p<0.0001), and HU6 vs. placebo (-6.5 pounds, p=0.0003).

- Fat-selective weight loss: significant reduction in visceral fat from baseline with HU6 (-1.5%, p<0.0001), and HU6 vs. placebo (-1.3%, p=0.003).

- Reduction in abdominal visceral adipose tissue with HU6 vs. placebo (-0.19 L) in patients assessed with MRI for body composition.

- No significant change in lean body mass or skeletal muscle mass compared with baseline

Regeneron, phase 2 COURAGE trial: trevogrumab (anti-GDF8/anti-myostatin), or trevogrumab plus garetosmab (anti-activin A), in combination with semaglutide – interim results [7]:

- Both dual and triple combinations increase weight loss vs. semaglutide monotherapy, with observed percentage change in body weight from baseline at 26 weeks of 11.3% for trevogrumab plus semaglutide, 13.2% for trevogrumab plus garetosmab and semaglutide vs. 10.4% for semaglutide monotherapy.

- Both dual and triple combinations increase loss of fat mass vs. semaglutide monotherapy, with observed reduction in fat mass as % of total weight loss at 26 weeks of 75.3% for trevogrumab plus semaglutide, 84.4% for trevogrumab plus garetosmab and semaglutide vs. 66.3% for semaglutide monotherapy.

- Both dual and triple combinations preserve lean mass vs. semaglutide monotherapy, with observed preservation of lean mass vs. semaglutide monotherapy at 26 weeks of 51.3% for trevogrumab plus semaglutide and 80.9% for trevogrumab plus garetosmab and semaglutide.

Scholar Rock, phase 2 EMBRAZE trial: myostatin inhibitor apitegromab plus trizepatide [8]:

- Patients on apitegromab plus trizepatide achieved 12.3% weight loss at week 24 vs. 13.4% for tirzepatide plus placebo.

- Selective weight loss: Only 14.6% of total mass lost was lean mass for apitegromab plus trizepatide vs. 30.2% for tirzepatide plus placebo, which equates to statistically significant preservation of lean mass of 1.9kg, or 54.9% vs tirzepatide and placebo.

Lilly, phase 2 BELIEVE trial: activin type II receptor inhibitor bimagrumab plus semaglutide [9]:

- Increased weight loss: 22.1% for bimagrumab plus semaglutide vs. 15.5% for semaglutide monotherapy at 72 weeks.

- Fat-selective weight loss: 92.7% of lost weight was fat mass for bimagrumab plus semaglutide vs. 71.8% for semaglutide monotherapy.

- Increased reduction in abdominal visceral adipose tissue: 58% for bimagrumab plus semaglutide vs. 36% semaglutide monotherapy.

- Quality of life: statistically significant improvement in physical function score (using Quality of Life Short Form 36) for bimagrumab plus semaglutide vs. semaglutide monotherapy; but not when measured using Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite for Clinical Trials (IWQOL‐Lite‐CT).

These promising mid-stage trial results demonstrate the role pharmacotherapies can play in improving the quality of weight loss by preserving muscle mass.

However, confirmatory data from larger phase 3 trials will be needed to substantiate the potential of muscle-preserving investigational therapies to address likely questions from regulators, for example around longer-term safety and efficacy, and variations across different sub-populations.

Furthermore, it is possible regulators may require evidence of additional benefits beyond body composition for the approval of muscle-preserving therapies, such as incremental weight loss above background therapy for combinations or patient-relevant outcomes.

Seizing the commercial opportunity

For muscle-preserving therapies to fulfil their potential, innovators must focus on three priorities as their assets advance through the pipeline:

- Evidence beyond body composition: Demonstrating patient-relevant functional benefits is critical for gaining market access in the reimbursed market, ensuring willingness to pay in the out-of-pocket market, and for the adoption of muscle-preserving therapies in clinical practice. Examples of patient-relevant benefits include the six-minute walk test, hand-grip strength, stair climbing, gait speed or the ability to perform activities of daily living.

Digital endpoints combined with wearables offer unique opportunities for the longitudinal collection of relevant functional data in a patient’s everyday life.

Furthermore, health systems will be interested in understanding the wider benefits of such therapies, e.g., potential cost offsets and lower healthcare resource utilisation from preventing downstream complications of sarcopenia. Health economics data demonstrating reduced costs of care for the elderly obese due to improved levels of activity and self-care will be important for securing reimbursement.

Finally, with typically older, multi-morbid, obese patients the primary target segment for muscle-preserving therapies, long-term safety and tolerability data, including in polypharmacy situations, are a key prerequisite for their wider adoption, to address lingering concerns about some of the mechanisms of action being explored. - Segmentation and positioning: Commercial success depends on the careful positioning of muscle-preserving therapies against the often complex unmet needs of specific obese patient segments which are defined by multiple dimensions, e.g., BMI, age, presence of several co-morbidities or pathophysiological phenotypes.

Furthermore, with numerous new weight loss therapies poised to enter the obesity market in near future, by the time muscle-preserving therapies launch they will need to navigate and co-position themselves against a crowded and fluid treatment landscape.

This will require granular strategic patient segmentation informed by multiple data sources with RWD playing a key role, e.g., anonymised, longitudinal patient-level Rx data, claims data or EMR, combined with primary market research. This segmentation needs to establish where and how muscle loss manifests itself in a real-world setting to prove and pin-point unmet need, enable precision positioning and the articulation of compelling, patient segment-specific value propositions. - Market shaping: Muscle-preserving therapies represent a novel treatment approach and will enter a market that to date has largely focused on quantity of weight loss, not quality. Therefore, successfully launching new muscle-preserving therapies will require extensive market shaping activities to create awareness of unmet need around the risk and implications of muscle loss, to build advocacy for the need to treat, the role of novel pharmacotherapeutic approaches and their clinical, economic and patient-relevant benefits.

Furthermore, as HCPs lack prior experience with muscle-preserving therapies, innovators will need to provide practical education on when and how to use such therapies, likely alongside other AOMs, including diagnostic approaches to identify eligible patient segments in routine practice. There will likely be considerable overlap between sarcopenic patients and the elderly at risk of or suffering from osteoporosis, especially among women. Therefore, future therapies with the potential for both bone and muscle sparing properties would be particularly interesting for this segment.

Innovators will also need to reassure HCPs about the safety of these new therapies to address potential concerns or overcome pre-conceptions. Medical affairs will play a critical role in delivering these activities.

A multi-asset portfolio strategy will be an important consideration, especially for those innovators with muscle-preserving agents that will be positioned as adjunct therapies to incretin-based AOMs, e.g., being able to synergistically combine proprietary therapies to offer value propositions tailored to the needs of sarcopenic, obese patient segments, without dependence on third parties for a foundational incretin therapy.

As the obesity market continues to evolve beyond its initial hype phase which was dominated by a singular focus on ever greater weight loss achieved, the quality of weight loss is increasingly being recognised as an equally important goal.

Several innovators have embraced this opportunity, while recent mid-stage trial readouts have offered a glimpse of the potential that novel muscle-preserving therapies hold. As these assets progress through clinical development towards approval, and ultimately market entry, will they fulfil their promise? No doubt, addressing the quality of weight loss continues to be an intriguing field to observe.

References

- FDA: Developing drugs and biological products for weight reduction; draft guidance for industry, January 2025: https://www.fda.gov/media/71252/download

- Žižka O, Haluzík M, Jude EB. Pharmacological Treatment of Obesity in Older Adults. Drugs Aging. 2024 Nov;41(11):881-896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-024-01150-9

- Benz E, Pinel A, Guillet C, et al. Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity and Mortality Among Older People. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243604. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3604

- Murdock, D.J., Wu, N., Grimsby, J.S. et al. The prevalence of low muscle mass associated with obesity in the USA. Skeletal Muscle 12, 26 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13395-022-00309-5

- Veru press release, 28 May 2025: Veru Reports Positive Safety Results from Phase 2b QUALITY Study: Enobosarm Added to Semaglutide Led to Greater Fat Loss, Preservation of Muscle, and Fewer Gastrointestinal Side Effects Compared to Semaglutide Alone

- Rivus Pharmaceuticals press release, 30 September 2024: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/rivus-pharmaceuticals-announces-new-clinical-data-from-phase-2a-humain-trial-demonstrating-significant-weight-loss-with-hu6-in-patients-with-obesity-related-heart-failure

- Regeneron press release, 2 June 2025: Interim Results from Ongoing Phase 2 COURAGE Trial Confirm Potential to Improve the Quality of Semaglutide (GLP-1 receptor agonist)-induced Weight Loss by Preserving Lean Mass | Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

- Scholar Rock press release, 18 June 2025: https://investors.scholarrock.com/news-releases/news-release-details/scholar-rock-reports-positive-phase-2-embraze-trial-results

- STAT article, 23 June 2025: New Eli Lilly drug could help prevent muscle loss while taking a GLP-1 | STAT