- Blogs

- IQVIA Thought Leadership COVID-19 vaccination review: 6 months of rollout tracking, 6 key observations

IQVIA’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout tracker

For six months now IQVIA has developed a biweekly overview of global COVID-19 vaccine rollout progress powered by Our World In Data (OWID) data, an open source repository of rollout data from public and governmental sources. OWID’s database is curated by a team at the University of Oxford and provides a rounded global view of COVID-19 vaccine rollout updated daily. This review aims to highlight key insights from the first six months of vaccine rollout, not provide a current view of rollout progress, and is therefore based on data from early June (03/06/2021).

Rollout metrics define our perspective

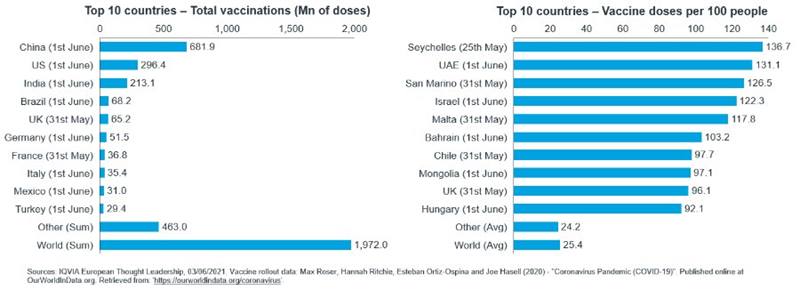

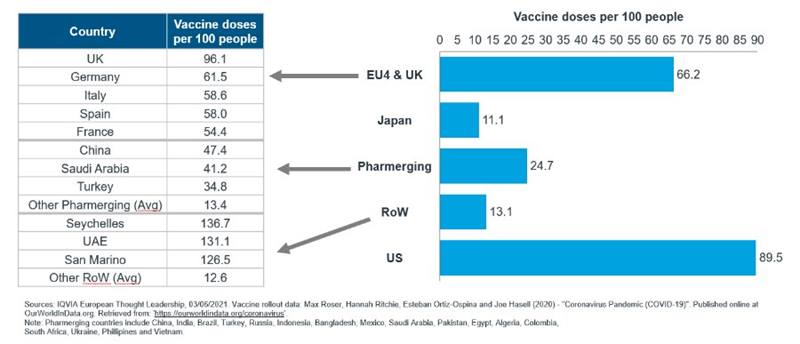

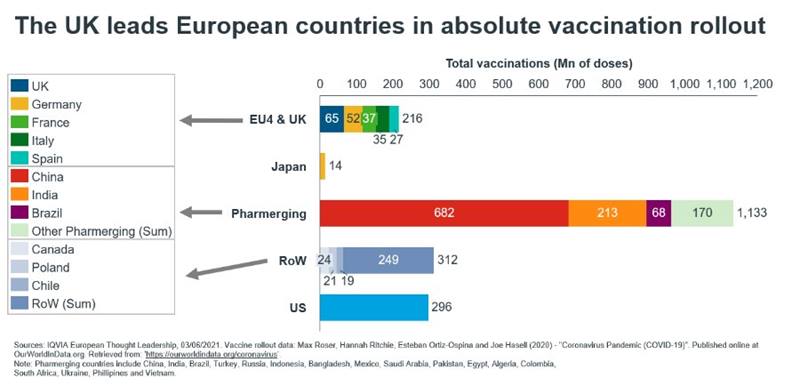

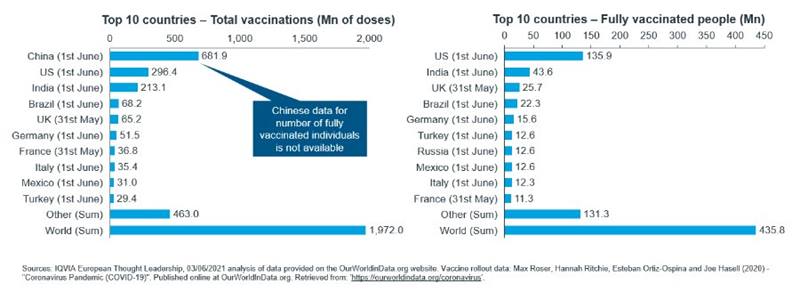

Our COVID-19 vaccine tracker has highlighted the importance of choosing the most appropriate metric when analysing national rollout data. Absolute and per capita vaccination metrics both offer useful but alternative views of vaccine rollout progress and must be interpreted accordingly. Absolute rollout metrics (how many doses have been administered) are driven by national procuring power as well as distribution and administration efficiency. These factors also drive per capita rollout once population size is accounted for. Overall, per capita metrics are arguably more useful as they best reflect progress towards achievement of herd immunity, the hopeful end goal of vaccine rollout.

Choice of metric enable a nation’s rollout progress to be viewed in a different light. For example, a country with a high population and large absolute number of vaccines rolled out may highlight the achievement of rolling out a comparatively large number of administered vaccines but % population coverage may lag.

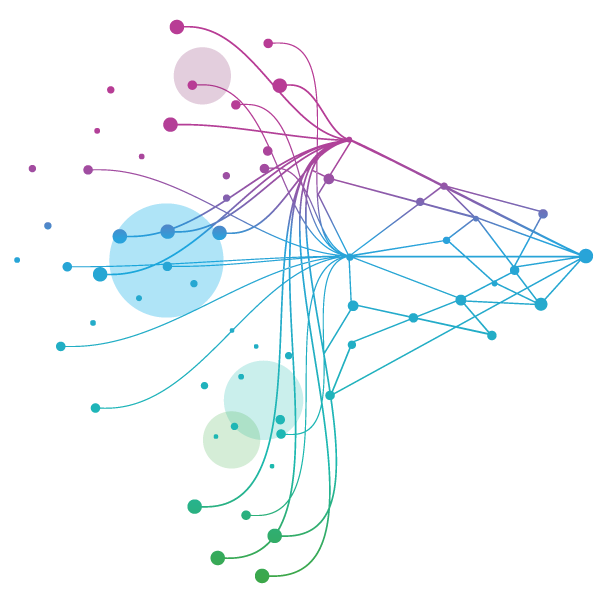

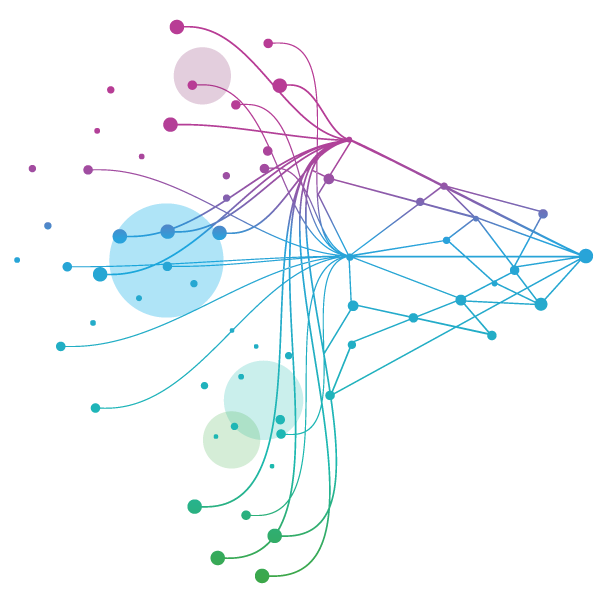

Differences between rollout metrics are apparent in the vaccine tracker; countries with large populations and GDPs often rank highly by absolute rollout statistics whereas countries with smaller, dense populations rank highly in per capita terms (Figure 1).

Global rollout is widely variable

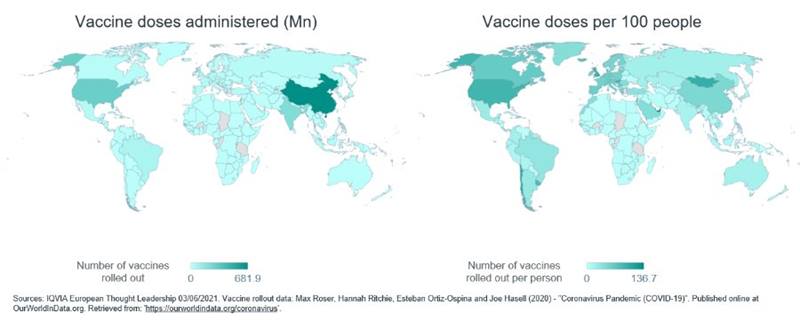

It is widely reported that vaccine allocation is not equal between nations by neither absolute nor per capita measures of rollout.1,2. Equity is potentially more important than equality in vaccine allocation; some countries will have a disproportionally greater need for vaccines. For example, some countries may be more able to enact alternative anti-COVID-19 measures and national health systems may have varying capabilities to manage infection spikes.

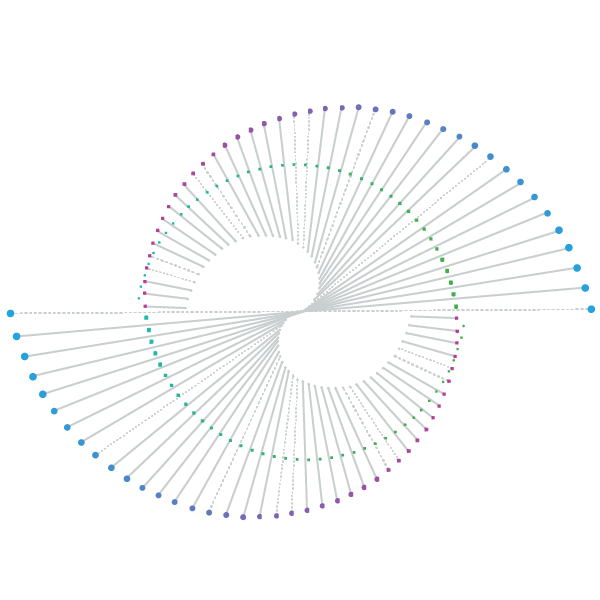

Patchy global rollout is evidenced in the tracker (Figure 2) and driven by multiple factors acting on a national level including:- Availability of vaccines: Number and scope of supply agreements with vaccine companies determines access. Additionally, local, or state-owned manufacturing of vaccines, needles and vials, or other accompanying materials can expedite rollout.

- Regulation of vaccines: Efficient local regulators decrease wait time for vaccine authorization and distribution. Approval of single dose vaccines or vaccines best suited to the local climate or storage capacity will aid rollout.

- Distribution infrastructure: Some vaccines require ultra-cold storage and all vaccines require suitable sites to host vaccinations.

- Availability of vaccination personnel: HCPs or trained individuals are required to administer vaccines.

- Population and geography: Small, densely located populations ease distribution. Countries with warmer climates face greater cold-chain challenges. Local cultural factors such as vaccine hesitancy can hamper rollout.

- National wealth: National wealth is required to finance all the above factors of rollout and overcome barriers. GDP per capita is likely to be more important than GDP alone for successful rollout due to population vaccine coverage being the critical factor in reducing spread and disease.

As national wealth is a key determinant of success across all aspects of rollout (vaccine acquisition, distribution, and administration) it is generally skewed towards wealthier countries. Absolute rollout rankings are skewed towards countries with a large GDPs as these countries have the finances and power to either produce vaccines domestically, e.g. India and China, or bid for supply agreements, e.g. the US and the UK (Figure 1). Per capita rollout rankings often feature countries with smaller populations and GDPs but higher GDP per capita, for example San Marino and the UAE; high GDP per capita countries can spend proportionally more resources to vaccinate each individual citizen (Figure 1). These trends are further illustrated by comparisons of rollout between global regions; rollout is heavily

Figure 3. Regional inequality in vaccine rollout highlights the influence of national wealth on rollout potential.

skewed on a per capita basis towards wealthier European countries and the US (Figure 3). Pharmerging countries with large populations and GDPs but lower GDP per capita rank highly for absolute rollout but not in per capita terms (Figure 3).

Not all inequality and inequity are can be attributed to the drivers described above as other less systemic factors such as vaccine diplomacy can be impactful. For example, high ranking of the Seychelles on a per capita basis is primarily due to vaccine diplomacy originating in India and the UAE (Figure 1)3,4 . Mongolia also ranks highly by vaccines per capita despite low national wealth. Situated between Russia and China, both of which are vying for strategic influence, Mongolia has benefited significantly from vaccine diplomacy receiving supplies of both Sputnik V and Sinopharm as a mix of donations and expedited deals5.

Organisations such as COVAX, the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access initiative, are working to avoid and remedy vaccine inequality on a global basis by supplying vaccine-poor countries. However, at six months of rollout tracking, COVAX has distributed only ~85 Mn vaccines, similar to the number of vaccines rolled out in Brazil alone, due to vaccines supplies being focused in a group of influential and wealthy nations6. Despite donations to struggling countries and to COVAX, vaccine-rich countries are still often vaccinating their younger less vulnerable populations while rollouts elsewhere are still in their infancy7.

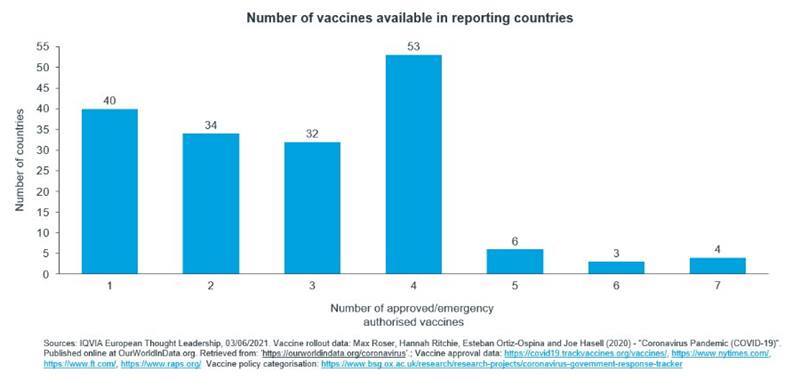

Countries are opting to approve multiple vaccines

IQVIA’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout tracker includes a measure of vaccine approvals by country and has illustrated an expected increase in the average number of approvals per country. Most countries have now approved more than one vaccine (Figure 4). Approving multiple vaccines offers the strategic benefit of non-reliance on a single product. Assuming supply agreements are secured, the availability of vaccines can still fluctuate due to disruptions in manufacturing and delivery as well as limitations on usage due to safety concerns. Additionally, although not a pertinent factor yet, future COVID-19 variants may evolve resistance to some vaccines making reliance on a single vaccine risky. Finally, theories regarding the immunological benefits of vaccine dose mixing which have been touted previously were recently supported further by study evidence8,9; if multiple vaccines are approved this enables possible dose mixing.

The ability to approve a vaccine or multiple vaccines is skewed towards wealthier developed countries which generally host well-funded and therefore faster acting regulatory bodies.

Less developed nations may have to wait for the WHO to provide a recommendation which often takes more time than regulators such as the FDA and EMA. A nation’s development status can therefore indirectly impact vaccine rollout by affecting the number of vaccines approved and which are available for use.

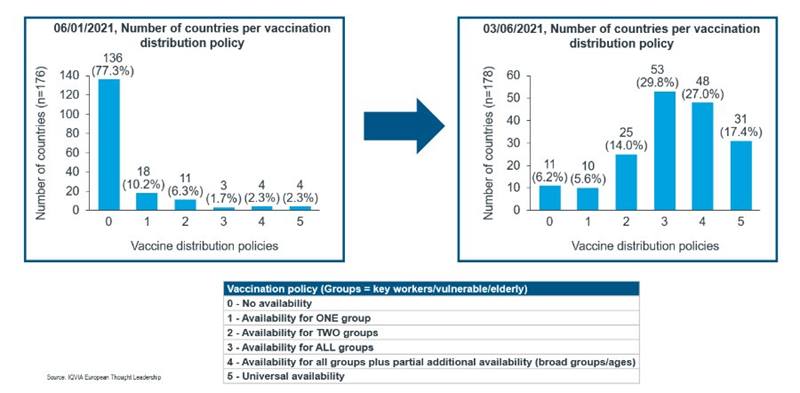

Vaccine distribution policies are loosening as rollout proceeds

As the tracker has monitored the progress of vaccine rollout since January 2021 it has become apparent that intranational restrictions on vaccine distribution are becoming less stringent (Figure 5). Initially all countries employed a policy of restricting vaccine administration to certain populations which offered the greatest perceived strategic benefit of being protected from COVID-19. For most countries this manifested as targeting of demographics which are most likely to become seriously ill in response to infection by COVID-19 for example the elderly or those with underlying health conditions. Most countries also targeted HCPs due to their high risk of infection and likelihood of acting as transmission vectors.

The shift towards broader intranational distribution can be a sign of successful or failed epidemic control. In some European countries and the US, all vulnerable citizens have been vaccinated, or at least offered the vaccine, and government vaccine rollouts are now targeting younger healthy people; rollouts are being extended to those less in need of a vaccine as the vulnerable are already protected10,11,12. Expansion of distribution is not however always a sign of rollout completion; in India access to free government vaccines has recently been extended to all adults in response to a critical wave of infections and deaths13.

Despite global trends the local pandemic situation and government decisions can lead to unique distribution scenarios. Indonesia’s initial rollout provided a notable exception to global vaccine targeting by initially prioritising the working population instead of the elderly14. The rationale behind this decision was a lack of information regarding the Sinovac vaccine’s efficacy in the elderly plus a desire to kickstart the economy and vaccinate the population with the greatest tendency to socialise. The Indonesian government’s decision was however reversed in February and the elderly began to be prioritised alongside key workers but after HCPs15.

Dosing policies complicate assessment of rollout progress

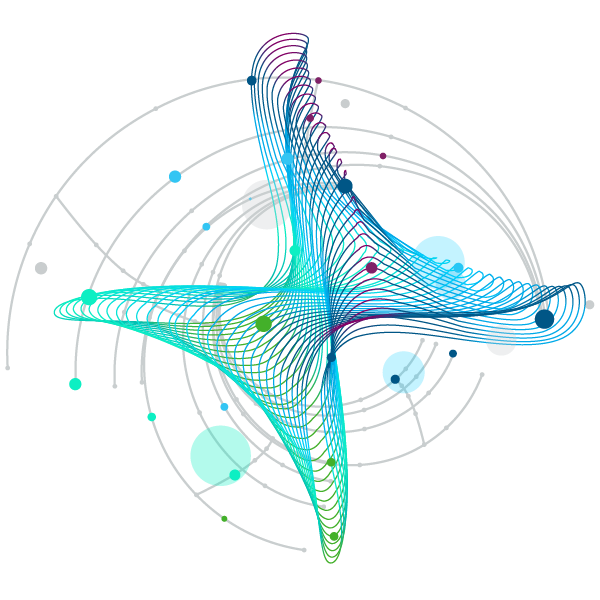

COVID-19 vaccines, except for Johnson & Johnson’s product, are designed to require two doses for optimal protection. The timing and type of these two doses can be altered creating another factor contributing to rollout efficiency. Different governments have opted for different periods of time between the two doses, some have followed the label recommendation whereas others have extended the inter-dose period. Variation in national dosing policies results in a disparity between number of doses administered and the number of fully vaccinated individuals (Figure 6); number of fully vaccinated individuals is not simply half the number of doses administered.

The immunological benefits of different dosing periods are still in contention, however, countries which have opted for dosing periods longer than that recommended by the manufacturer have still hosted successful rollouts. Most famously the UK government made the early decision to opt for 12 rather than 3 week spacing between doses and has still benefitted from an efficacious rollout16,17. Despite it being unknown whether the spacing between doses impacts degree of immunity or its longevity there are other possible drivers to opt for different dosing policies; more widely spaced dosing allows greater population coverage but with a lower level of protection and vice versa. For example, in the initial UK outbreak a single dose was found to reduce serious illness and hospital admissions meaning widespread one dose coverage reduced pressure on the national healthcare system at a time of acute strain. Whether waiting longer between doses is wise depends on several factors including whether dose spacing impacts the degree and longevity of immunity, as well as how efficacious the vaccine being used is after one versus two doses.

Policies on vaccine dosing must account of changes in the virus itself. New variants may change the balance of benefits offered by different dose spacings. Most recently vaccines were shown to be efficacious versus the novel Delta (Indian) variant, however, while protection provided by two doses of AstraZeneca’s vaccine was similar to other variants protection after just one dose was reduced18,19. National policies must therefore take such evolutions into account and adjust policy accordingly. The UK government responded to lower single dose efficacy versus the Delta variant by encouraging citizens to ensure they receive their second jab.

In addition, there is the option to administer a second dose of a different vaccine type to the first, often know as mix-and-match dosing. Mix-and-match dosing offers dual benefits, one certain and the other a potential. The ability to mix-and-match vaccine products offers a similar benefit to approving multiple vaccines; non-reliance on a single vaccine solution is beneficial if a previously used product’s supply is interrupted by manufacturing delays or safety concerns. Secondly, the potential benefit of increased immunity following vaccination with two doses of different jabs is uncertain but increasingly supported by evidence (see above).

The Johnson & Johnson single dose vaccine offers simplification of the administration procedure which may be especially important in countries with poor healthcare infrastructure. Overwhelmed health systems with limited storage, vaccination sites, and number of HCPs may benefit from a one dose solution.

Vaccine acceptance is heterogeneous

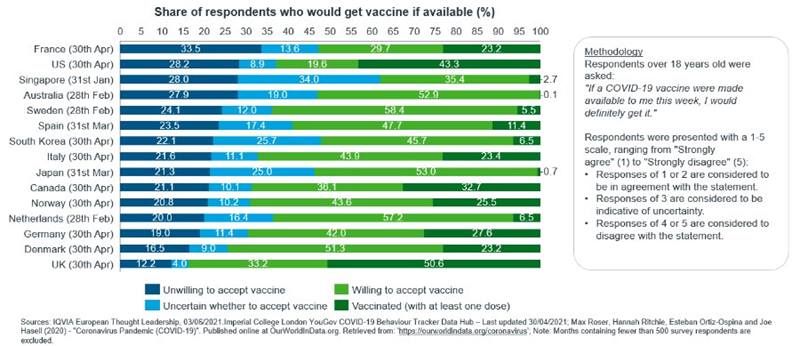

In addition to monitoring rollout of vaccine doses the IQVIA Thought Leadership tracker also presents data regarding vaccine acceptance in a range of developed nations. Levels of vaccine acceptance have remained constant for some countries but not others and it would be inappropriate to speculate which events in the news cycle prompted such changes in opinion. Fake news, political developments, historical events, and real reported adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccinations all impact the public’s view of whether vaccination offers a great enough benefit to accept the perceived and real risks.

Vaccine acceptance is a final hurdle to rollout. Even in an optimal situation of unlimited vaccine supply and distribution capacity vaccines are useless if willing recipients are unavailable. Levels of population vaccine acceptance is determined by multiple factors including:- Perceived health benefits to themselves and others - Dependent on perception of potential danger posed by COVID-19 infection versus potential harm of vaccination.

- Other perceived benefits of vaccination to themselves and others – A reduced need for social distancing and other restriction provides an incentive for vaccination.

- Government or corporate policies encouraging vaccination – Governments or private companies may restrict the liberties of those who remain unvaccinated.

- Effort/ cost of vaccination – All vaccinations will incur a time cost, and in some countries vaccinations may in incur an individual financial burden.

- Misinformation and fake news – Relative exposure to scientific/ medical information versus fake news and misinformation.

- Other more nebulous factors – An individual’s religious beliefs, cultural norms, or fear of needles/ doctors may present barriers to vaccination.

Survey data available in the tracker reveals that, among the surveyed countries, vaccine acceptance is not a product of the simpler trends such as wealth, geography, or population size which influence other aspects of rollout. Similar countries have very different levels of vaccine acceptance, for example high and low acceptance in Germany and France respectively. Here two countries of similar GDP/ capita, population size, and location hold notably different cultural views of vaccination.

Interestingly the local severity of the pandemic does not appear to clearly impact vaccine acceptance either. Countries which have had significant levels of COVID-19 such as the US or those which have escaped relatively unscathed such as Singapore both exhibit low vaccine acceptance. Conversely vaccine acceptance is higher in hard hit countries such as the UK and in countries which have fared better such as Norway.

A final point of note is that polling of vaccine acceptance is not available on the granular level of individual products. It is likely that, due to media coverage and comments from politicians, vaccine acceptance would differ significantly between different brands.

Outlook

Looking to the future it remains uncertain whether global herd immunity will ever be achieved. Rate of global rollout has entered a steady state in May-July 2021 and if extrapolated this rate will result in every global citizen receiving two vaccines, the most common dosage, by mid-2022. The adult population could be vaccinated before this point, but an unvaccinated pool of young people will still incubate and circulate COVID-19 leading to a continued healthcare threat. Complete global coverage is however unlikely to be achieved on this timescale due to continued lack of vaccine supply in some countries while others use more than two vaccines per citizen to build stockpiles or administer boosters. Equally, some individuals will refuse vaccines while for others medical reasons will prevent them from receiving a vaccine or developing robust immunity following vaccination. As vaccine rollout continues boosters are likely to be implemented to top-up existing immunity, combat waning immunity, and react to COVID-19 variants which partly evade the efficacy of existing vaccines.

The dynamism and uncertainty of vaccine rollout highlights the importance of IQVIA’s vaccine tracker. Vaccine rollout tracking is vital for the pharmaceutical industry due to the direct and indirect impact of vaccine spend as well as the progression towards herd immunity and the easing of restrictions. Once the most acute stages of the pandemic are overcome the healthcare new-normal can be assessed and embraced.

Sources

1 https://www.who.int/campaigns/annual-theme/year-of-health-and-care-workers-2021/vaccine-equity-declaration2 https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/ecosoc7039.doc.htm

3 https://www.wsj.com/articles/covid-19-vaccines-are-becoming-important-diplomatic-currency-11613152854

4 https://apnews.com/article/seychelles-herd-immunity-mid-march-eba7c404b4530e9cc15d2e5dd1df6f58

5 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/20/business/coronavirus-vaccine-mongolia.html

6 https://www.gavi.org/covax-vaccine-roll-out

7 https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches

8 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01359-3

9 https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.01.21258172v1.full.pdf

10 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/adolescents.html

11 https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-57388643

12 https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals

13 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/57400891

14 https://fortune.com/2021/01/11/covid-vaccine-elderly-young-youth-indonesia-sinovac/

15 https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesia-aims-speed-up-vaccinations-jakarta-opens-over-18s-2021-06-09/

16 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-57073312

17 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)00455-4/fulltext

18 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-57214596

19 https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/current-covid-vaccines-appear-protective-against-variants-who-europe-says-2021-05-20/