Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (simply referred to as Alzheimer’s) is a progressive neurodegenerative protein-misfolding disorder with cognitive, functional and behavioral alterations. Alzheimer’s is predominantly age related and is becoming markedly more common with the aging of the world's population. Alzheimer's is ranked as the sixth leading cause of death in the USA. More than 6 million Americans have Alzheimer’s and it is estimated that by 2060, there would be approximately 15 million patients with the disease in the USA. It is the cause of 60-70% of cases of dementia.

The pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s is complex and is still being unraveled. Alzheimer's is characterized by the presence of amyloid plaques (amyloid β) and neurofibrillary (tau) tangles, leading to the progressive loss of neurons and synapses in the cerebral cortex and certain subcortical regions. The disease course is divided into three stages based on a progressive pattern of cognitive and functional impairment: the preclinical stage without symptoms (cognitively normal), prodromal stage with mild cognitive impairment, and the advanced stage of Alzheimer's with cognitive and functional decline that is stratified into mild, moderate and severe phases.

The cause for most Alzheimer's cases is still mostly unknown except for 1-5% of cases where genetic factors have been identified. APOE4 is the major genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s. Various competing theories based on amyloid, tau, and neurovascular involvement have been postulated to explain the fundamental cause of the disease.

Landscape of Alzheimer’s therapies: mushrooming pipeline but frequent failures

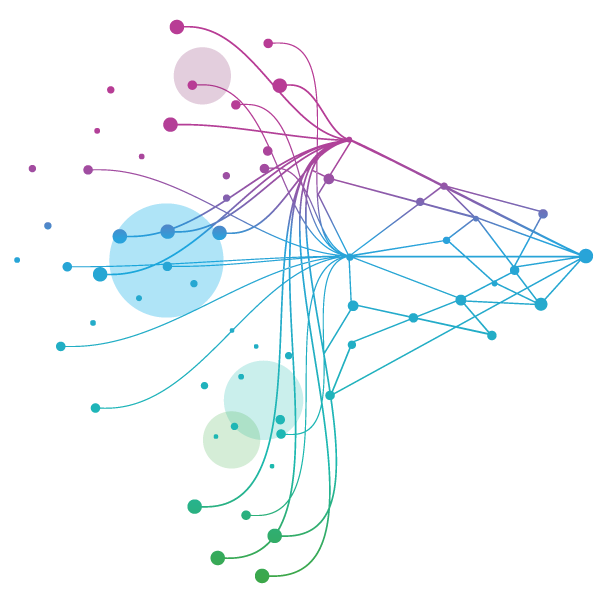

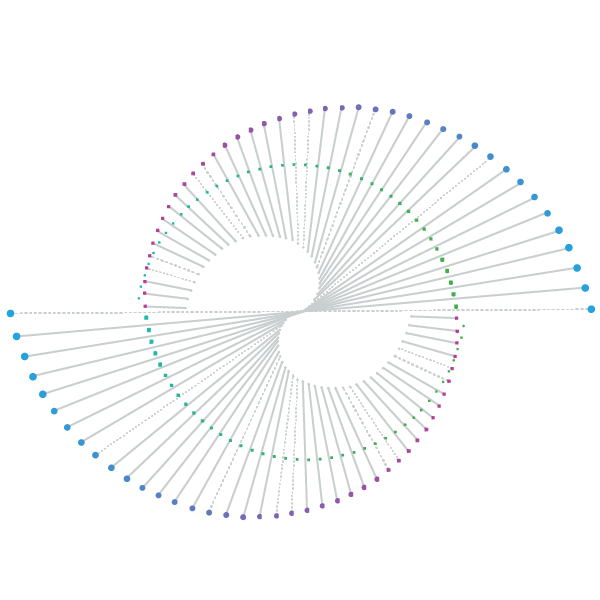

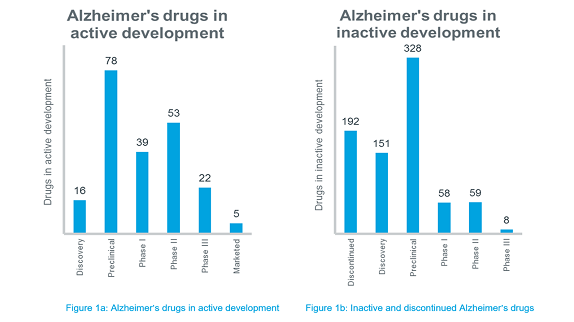

There is no cure for Alzheimer's. Available treatments offer relatively small symptomatic relief but remain palliative in nature. Although there are many novel molecules that are being investigated for Alzheimer’s, around 200 candidates have been either abandoned in development or have failed in late-stage clinical trials. Many candidates that were under development are now deemed inactive because no further developments have been reported for the past 3 years. The phase-wise distribution of all the Alzheimer’s drugs available in IQVIA™ Pipeline Intelligence is depicted in Figure 1a and 1b.

Impasse in Alzheimer’s landscape

As evident from Figure 1b, the development of Alzheimer's drugs has been marred by a high failure rate. A study revealed that Alzheimer's clinical trials fail at a rate of 99.6% compared to a failure rate of 81% for cancer drugs. In the recent years, several of the major pharma companies have aborted large phase III trials in Alzheimer’s. No new molecular entity for treating Alzheimer’s has been approved since 2003 and not one disease-modifying drug for Alzheimer's has been approved, despite many long and expensive trials.

Disease-modifying drugs aim to block progression of the disease by interfering with the pathogenic steps responsible for the clinical symptoms, including the deposition of extracellular amyloid β plaques and of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, inflammation, oxidative damage, iron deregulation and cholesterol metabolism. The approved drugs for symptomatic management are not so effective. The current Alzheimer's clinical research stalemate has encouraged more physicians to recommend lifestyle modification as non-pharmacological alternatives for the disease management.

With the repeated failures in the past years in the class of anti-β-amyloid monoclonal antibodies and γ-secretase inhibitors, focus shifted towards alternate pathways such as β secretase/β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE-1). However, 2018 saw high-profile failures in clinical trials with BACE-1 inhibitors even in prodromal patients.

Eight of the drugs, mostly disease-modifying therapies, on which hopes have been pinned based on promising early-stage results, failed in phase III trials in 2018 and early 2019. These products failed either due to interim futility analysis confirming no favorable risk/benefit ratio or drug/placebo difference, or due to unacceptable toxicity. Underscored in 2018, developing Alzheimer’s drugs is a daunting task even for the top pharma companies and it is more impactful if the failure is so late at phase III.

Why the Alzheimer’s trials keep failing?

Why hasn’t the industry cracked the Alzheimer’s code? Many explanations have been proposed to explain failures of trials of disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer's as stated below:

- Alzheimer’s pathology is still a mystery and often the treatment too late: Alzheimer’s involves a part of the body that is still largely not understood, which hinders adequate understanding of the biology of Alzheimer's. Also, the interventions are started too late in disease development. Alzheimer’s pathology develops a decade or more before the appearance of symptoms.

- Amyloid hypothesis: The target most commonly focused on for Alzheimer’s drug development has been amyloid β plaques and their subsequent elimination. However, the disheartening failure of anti-amyloid drugs has posed the imminent question whether amyloid β is the correct target. Also, the anti-amyloid drugs do not restore the destroyed synapses or degenerated neurons that are responsible for disease’s catastrophic manifestations. Some posit that amyloid plaques might be just a symptom of Alzheimer’s instead of the cause. The predominant theory that accumulation of β-amyloid plaques is the driver of Alzheimer’s might be incorrect. Researchers are challenging its validity and gradually moving away from the earlier assumption of linear causality as proposed in the original amyloid hypothesis.

- Clinical trial design: The trials testing disease modifying drug effects require larger numbers of patients, larger numbers of clinical research sites and longer double-blind evaluations. The trials studying populations earlier in the course of Alzheimer’s, such as mild cognitive impairment and preclinical disease, should have longer follow-up to allow sufficient time to elapse to measure change. However, this increases the trial complexity and cost, and also results in a higher drop-out rate, placebo responses and life events that will undermine the results. Also, recruiting the wrong population (i.e. patients with advanced or early Alzheimer’s not adequately selected with biological markers such as amyloid deposition detectable by diagnostic tools) might lead to clinical trial failure.

- Outdated standards in measuring endpoints: Both the cognitive and functional endpoints often used in Alzheimer’s studies such as the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog scale), Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study - Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL) scale and Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB scale) may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect differences between study drug and placebo. In trials investigating early-stage cognitively normal or mildly impaired Alzheimer’s patients, the functional scales measuring any improvement in function will likely be of no benefit.

In March 2018 witnessing a steep rise in failure of trials, the US FDA recognized the urgent need for new medical treatments for Alzheimer’s and proposed changes in requirements of dual-endpoint of cognition and function in its draft guidelines, removing an unnecessary barrier to testing Alzheimer’s drugs. For trials testing stage 2 Alzheimer’s patients having biomarker evidence of the disease and subtle cognitive impairment, but no problems with function, the agency proposed to test only cognition as an endpoint. For trials evaluating stage 1 Alzheimer’s patients having no clinical symptoms of the disease, but having biomarker evidence of it, the agency proposed that improvements in relevant biomarkers could serve as a basis for accelerated drug approval.

Future directions

Although clinical trials of many agents over a wide array of mechanisms of action are being conducted, more than a decade has passed since any of these drugs received approval from the US FDA for Alzheimer’s. For refinement of clinical trials, an adaptive design can be followed by conducting interim analysis of data which allows modifications on sample size or dosage as the trial proceeds. Other avenues should also be explored and not just amyloid β drugs. The industry is exploring drugs acting on other targets such as tau aggregation inhibitors. There is research implying that epigenetic drugs such as those targeting Dkk1 gene might be impactful. The investigators are also conducting preventive trials in individuals with normal cognition but who carry the APOEɛ4 gene. Better diagnostic tools to detect the disease before it is too late to intervene should be developed. Effective genetic biomarkers must be employed for informing the correct population satisfying the inclusion criteria to achieve trial success. Even though no drug has entered the market in the last 15 years and the trials are fraught with setbacks, every unsuccessful trial is a learning opportunity and takes us closer to the next truly transformational and successful disease-modifying Alzheimer’s drug that might be approved for the treatment of this incurable disease.

Register to the INNsight Newsletter for regular patent, pipeline and conference updates.