Introduction

Almost 35 years ago, the US Congress introduced the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, that created a pathway for generic drugs to enter the market before the expiry of the innovator’s drug patents. The Hatch-Waxman Act allowed the generic companies to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with a Paragraph IV certification, stating that the innovator’s drug patents listed in the US Food and Drug Administration’s Orange Book (OB) are invalid, unenforceable or will not be infringed by the generic product. The submission of a Paragraph IV certification sets in motion a series of events eventually leading to the filing of an infringement proceeding in the District Court by the innovator company against the ANDA filer. For nearly three decades, this was one of the primary patent litigation frameworks available for challenging the validity of pharmaceutical patents.

More recently, the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) passed by the US Congress on 16 September 2011 and implemented a year later, brought about an alternative litigation pathway for the generic companies. The AIA introduced two new ways of challenging the validity of an issued patent - the Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post Grant Review (PGR) challenges. These post-issuance challenges replaced the earlier reexamination procedures available in the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) as it was felt that those procedures had become “too lengthy and unwieldy to actually serve as an alternative to litigation when users are confronted with patents of dubious validity.” The IPR and PGR proceedings are initiated in the USPTO before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), an adjudicatory board created by the AIA. These proceedings differ from conventional patent infringement proceedings, initiated in the US District Court by the innovator companies, as they are more cost-effective and time-saving.

Legal Procedure

IPR proceedings are initiated by a third party for cancellation of one or more patent claims as they are not patentable. However, there are stringent conditions for initiation of the IPR proceedings and the patent validity can be challenged only on the basis of:

- 35 US Code (USC) §102 (anticipation) and/or §103 (obviousness); and

- prior art that consists only of patents or printed publications.

The basis for raising PGR proceedings are comparatively lenient. The patent validity can be challenged on the basis of not only 35 USC §102 and §103, but also on §101 (subject matter ineligibility) and §112 (indefiniteness, lack of enablement, or failure to meet the written description requirement). Also, other than patents and patent publications the petitioner can also rely on evidences such as prior art public uses, on-sale activities and other public disclosures.

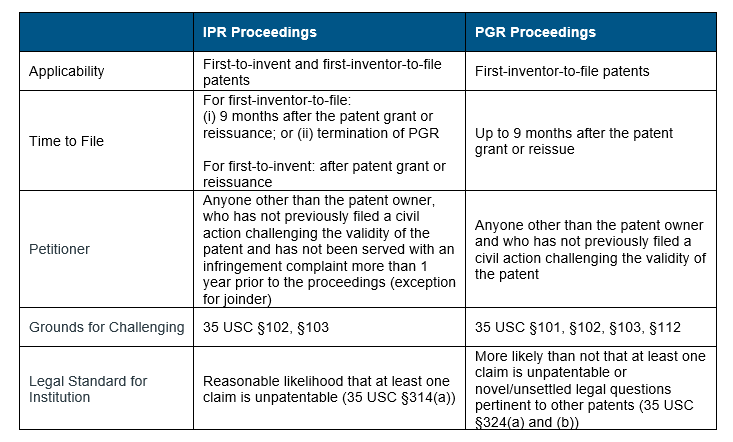

Other than the grounds for challenges, the IPR and PGR proceedings differ in several ways. Three primary differences are in relation to applicability, timing to file the petitions and legal standards for institution of the trials (Table 1).

For patent applications filed on or after 16 March 2013, the AIA moved the patent rights from ‘first-to-invent’ to ‘first-inventor-to-file’ system. This new system aligned the US patent rights system to that of the rest of the world. In the case of IPR proceedings, each system differs in their time to file: for patents filed on or after 16 March 2013, an IPR should be filed 9 months after the patent grant or reissuance or after the termination of a PGR proceeding, if one has been initiated; whereas for patents filed prior to 16 March 2013, they can be filed any time after the patent grant or reissuance. However, PGR proceedings are only available for patents with at least one claim filed on or after 16 March 2013 and must be initiated within 9 months from the grant or re-issue of the patent.

There are different legal standards for institution of IPR and PGR trials – for an IPR there must be “reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail with respect to at least one of the claims challenged in the petition” whereas for a PGR it must be “more likely than not that at least one of the claims challenged in the petition is unpatentable”. According to the USPTO, the “reasonable likelihood” standard encompasses a 50/50 chance that the petitioner would prevail to show that at least one challenged claim is unpatentable, but the “more likely than not” standard requires for the petitioner to show a greater than 50% chance that it would prevail. This higher legal standard makes the institution of PGR trials more challenging.

Table 1: Comparison between IPR and PGR Proceedings

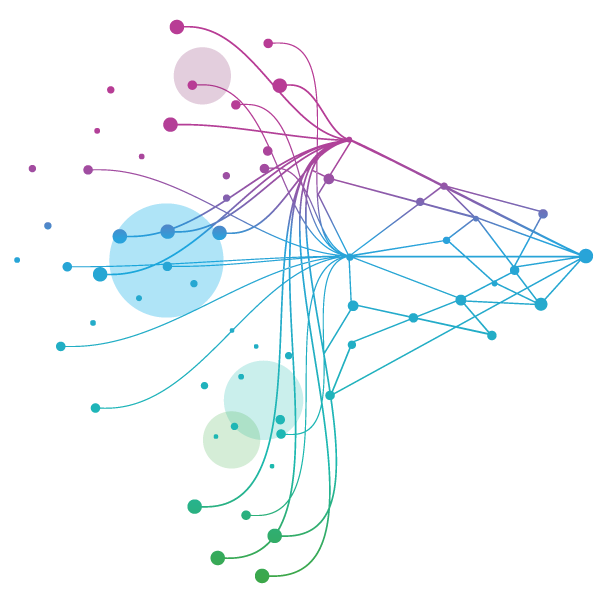

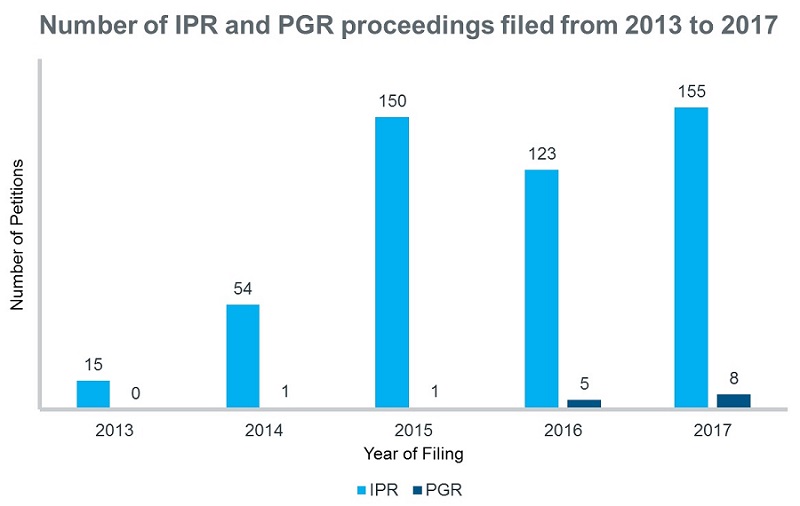

As an IPR proceeding can be filed any time, without any restriction on the type of patent system and with lower legal standards, they are quite a popular choice for the petitioners (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A comparison of the number of IPR and PGR proceedings filed from 2013 to 2017 according to Ark Patent Intelligence Litigation module

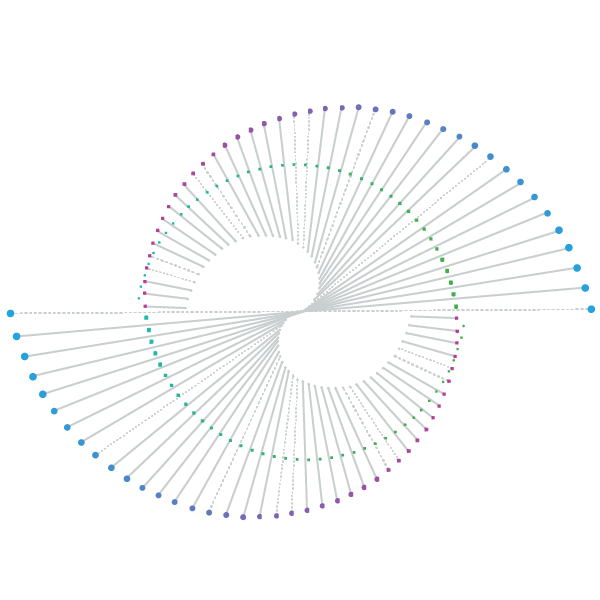

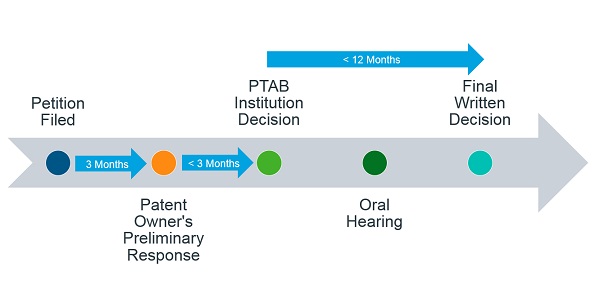

There are strict timelines that the PTAB follows during IPR and PGR proceedings (Figure 2). Both of these proceedings take the same amount of time – 12 to 18 months from the institution of the petition with an exception of up to 6 months for “good cause”. The proceedings are initiated when a petition is filed by a third party challenging the validity of a patent. Within 6 months of the petition being filed, the PTAB decides on whether the IPR should be instituted or dismissed. If the trial is instituted, the PTAB will issue a final written decision within 12 months of institution. Any party that is dissatisfied with the final decision may file for a rehearing with the PTAB within 30 days of the decision or appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) within 63 days. However, if the trial is not instituted on any challenged claim then the petitioner can seek for a rehearing with the PTAB within 30 days of the institution decision and if it is instituted on at least one challenged claim then within 14 days. Neither the institution decision nor the rehearing decision can be appealed to the Federal Circuit.

Figure 2: Typical Timeline of IPR and PGR Proceedings

Advantages of IPR and PGR Proceedings

The IPR and PGR proceedings provide a gamut of advantages to the generics over conventional civil actions. The main benefits are as follows:

- Cost: According to the American Intellectual Property Law Association’s “2017 Report of the Economic Survey”, the median cost of a Hatch-Waxman litigation was US$1.8 million for cases involving risks over US$25 million and for IPR proceedings through PTAB hearings was US$2.5 million. This shows that a civil action in the District Court can cost almost 7 times that of a proceeding in the PTAB.

- Efficiency: The IPR proceedings take about 12-18 months in the PTAB and an average of approximately 100 Hatch Waxman infringement proceedings (filed from 2012 onwards) covered on Ark Patent Intelligence Litigation module shows that the civil actions in the District Court can usually take up to 2.3 years. The time can be much longer, especially when bench trials are scheduled. Both these decisions can be appealed and can take additional time in the CAFC and Supreme Court.

- Legal Standards: The evidentiary standard for proving the patent invalid in the PTAB is “preponderance of evidence” (35 USC §316(e)), this is lenient compared to that of the District Court, where it is “clear and convincing evidence” (Microsoft Corp v i4i Limited Partnership, 2011).

- Expertise: The IPR and PGR proceedings are adjudicated by three administrative judges that have patent knowledge, which is not necessarily the case in District Courts.

The combination of these benefits makes these post-issuance patent challenges quite a lucrative choice for the generics and biosimilars looking to enter the market. One such drug that had a different outcome at the PTAB after failing at the District Court, is Rivastigmine.

Conclusion

The popularity of post-issuance challenges has been increasing since their inception in 2012. Although currently there are far fewer PGR than IPR proceedings filed, these are likely to increase as there will be more patents that will have at least one claim filed after 16 March 2013. Both proceedings provide a potentially cost and time-effective alternative for generic companies to challenge an issued patent and enter the market.

Register to the INNsight Newsletter for regular updates on patent intelligence.