- Blogs

- Future Biosimilar Opportunities

The next decade of biologics facing loss of exclusivity will define the opportunities available to biosimilar manufacturers. The US and Europe will be key markets but these present their own challenges.

A slow start

Biosimilar executives the world over are furrowing their brows. It has been over a decade since the first biosimilar was approved in Europe and the mechanisms for a profitable future are still far from certain.

Companies are pleased with the recent rapid uptake figures, led by the Nordics, UK and Germany, but the simultaneous slide in net price concerns them. Dominant payers have pushed discounts of the winning biologics past the 80% mark over the list price of the reference product. Lower-than-expected returns are unwelcome in an industry where regulatory uncertainty and rising costs of biosimilar development are a concern.

Uptake in the US hasn’t helped either. As of March 2019, nearly 30 months after launch, infliximab’s biosimilar share in the US was only 8%. In contrast, the share at the same time in the UK was 80% and Germany 45%. Compounding this are later entries for rituximab, trastuzumab and adalimumab compared to the EU. As such, companies that had factored a strong uptake in the US have had to recalculate which markets will allow them to recover their costs.

This has many wondering what future opportunities exist for biosimilar manufacturers. Will they be attractive enough to warrant the upfront costs or will we see a different model emerge from smaller, eastern players?

Future opportunities

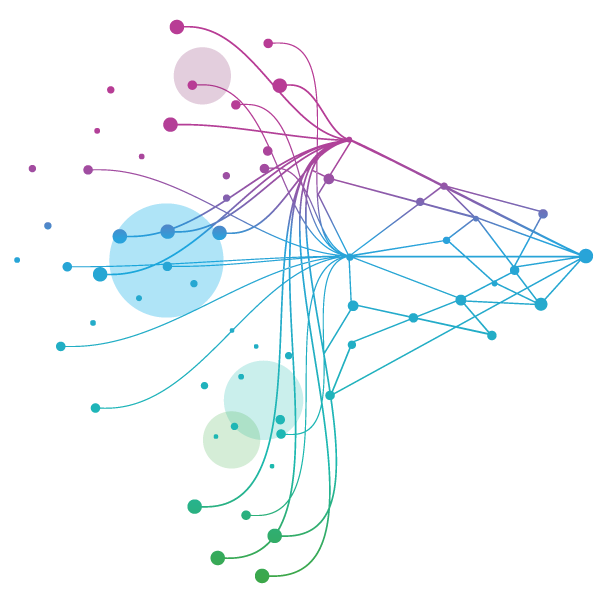

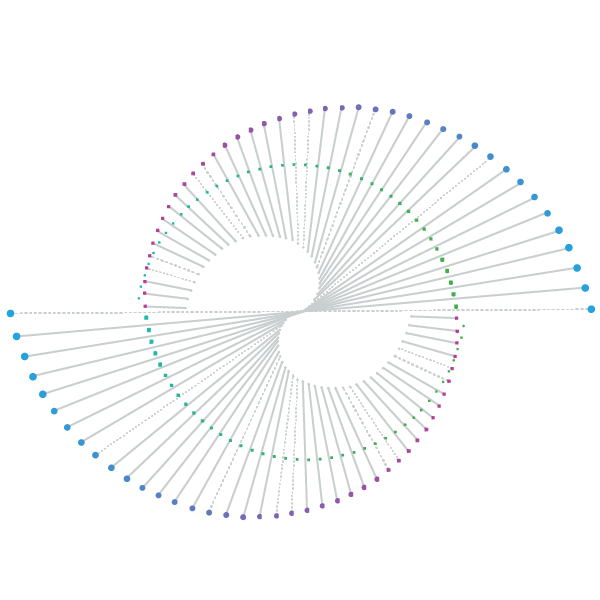

IQVIA Ark Patent Intelligence was used to determine a list of biologic molecules with a loss of exclusivity (LOE) date within the next decade (2020-2029). Forecasted sales from IQVIA Forecast Link for the originators at the year prior to LOE can determine the potential opportunity for biosimilars (Exhibit 1).

The most dramatic point to note from Exhibit 1 is that the largest opportunity for biosimilars will be in 2022-23 and 2028-29 and these spikes are driven by US sales of Humira and Keytruda respectively. Throughout the next decade, the US shows higher sales potential than Europe, helped by blockbuster products. Europe’s opportunities sit around the $3-5bn mark in each two-year cohort for the next decade. The LOEs for Keytruda and Opdivo sit outside the cohorts for Europe and are therefore omitted.

In the near-term, the 2020-21 cohort for the US is driven by Novolog and in Europe by Soliris.

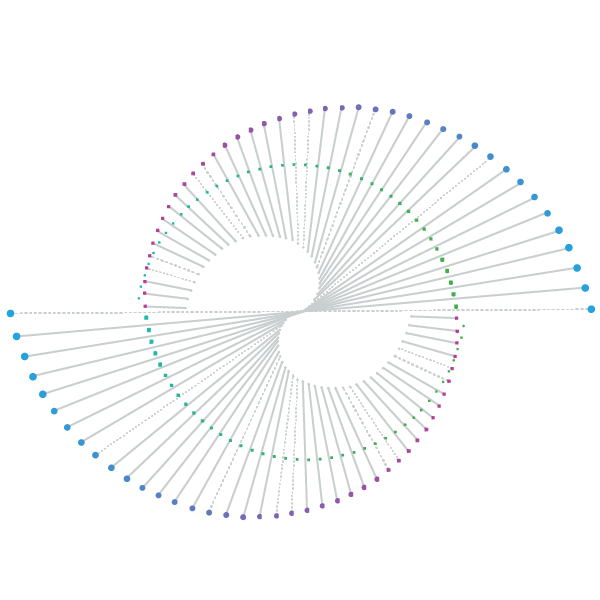

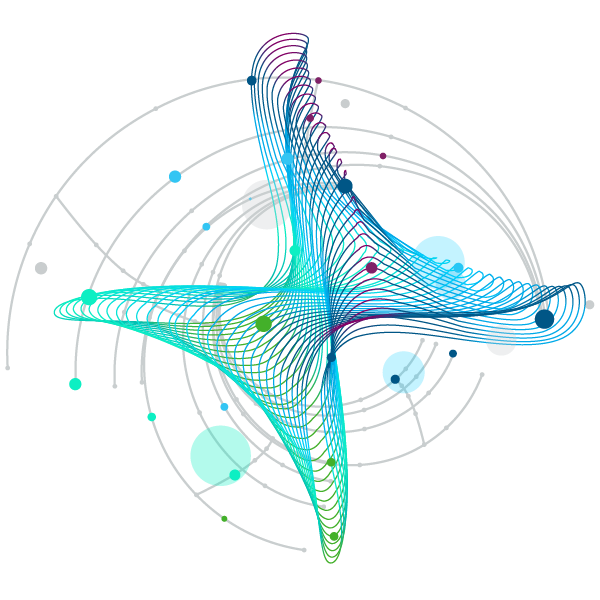

When the molecules are segmented by the magnitude of their sales (Exhibit 2), blockbusters Humira, Keytruda and Trulicity head the US’ dominance of multi-billion-dollar products. In Europe, the top three blockbusters are made up of Eylea, Stelara and Avastin.

The range between $100mn and $1bn contains the largest set of products such as Actemra/RoActemra in the US and Prolia/Xgeva in Europe. There are an even number of smaller opportunities (under $100mn) for both US and European regions.

Tomorrow’s battlefields

Truly global biosimilar prospects undoubtedly need viable access to the US market as it is home to the largest opportunities over the next decade. The European market, leading the way in access and innovative policies does not on its own offer a compelling market for large multinational players.

The blockbuster opportunities will be hard won by the largest players with substantial market access and marketing resources. These opportunities will see the largest number of competitors and therefore potentially offer the largest savings in price terms for healthcare systems. If pricing is held at a sustainable level and the US market opens up, then there are very compelling reasons to chase these products.

Interestingly, as of September 2019, the top US launch in 2019 from a sales perspective is a pegfilgrastim biosimilar Udenyca with $217mn, beating much-anticipated innovative products such as Skyrizi at $86mn. When a biosimilar is accepted by the country, it has the potential for wider adoption than other brands.

However, the battle for the $100mn-$1bn opportunities, of which the next decade shows the largest cohort of products, will be fought by a different mix of players. Asian manufacturers, especially from India and China, will look to prepare their biologics to export standards and operate, predominantly through market access partnerships, at a much lower cost base than western and large multinationals.

The upside for them is that the molecules they are competing for will remain attractive only to a few and so they have the opportunity to engage markets with little competition and so potentially command a greater price premium.

It is yet to be seen whether biosimilars will exist for products with sales of under $100mn. Unless we see the cost of biosimilar manufacturing, clinical trials and market access drop, the sales for these products may not make commercial sense and protect originators for longer. However, work is being done to explore biosimilars for orphan indications and return on investment will be a key component in these calculations.

The commercial future of biosimilars remains uncertain, at least for the large multinational players. Crucially, regulatory and payer policies will help foster an attractive environment, but this is also far from certain. Significant advocacy from patient and industry groups needs to convince market gatekeepers to create the mechanisms for a fair and sustainable industry.

Creating a new market is a slow process, it took the generics sector over a decade to establish itself as the major volume driver in developed markets and biosimilars are now facing this glacial acceptance by healthcare stakeholders.

The scaffolding erected by joint action between large cap industry, regulators and payers could be refined by smaller, more numerous opportunities which will form the bedrock for players from emerging markets. Only time will tell if enough groundwork has been done to enable a global market to flourish.

For more information on biosimilars, please reach out to me via email

- To read more on Humira biosimilars, click here for part 1 or here for part 2

- For Biosimilar Defence, click here

- To understand the Oncology biosimilars market, click here